WIN Waste completed upgrades to its waste-to-energy plant in Baltimore last month, making good on a deal with the city to lower emissions. The $45 million upgrade process, which began in 2022, required WIN to take each of the facility’s three boilers offline one by one, changing the facility’s filtration system from an electrostatic precipitator system to a fabric filter system.

On a May tour of the facility, WIN Waste employees showed Waste Dive the most recent upgrades to the facility, as well as other aspects of the facility that have been updated since it came online in 1985.

“This is the Ship of Theseus from the mid ‘80s to now,” Michael Dougherty, market manager at WIN, said on the tour. “So much has changed. Most importantly, emissions have changed dramatically.”

The facility had to temporarily stop accepting commercial waste from private haulers during the upgrades, which makes up roughly 40% of the waste WIN receives on a typical day. When at full capacity, the facility — which continued to receive waste from Baltimore City and Baltimore County during the upgrades as part of its contracts — receives upwards of 3,000 tons of waste per weekday. The three mass burn incinerators can process up to 2,250 tons per day, so on weekends, when the public customers don’t typically deliver waste, the facility makes up the excess.

The waste pit has an 8,000 ton capacity. The two 8-ton cranes — which are used to keep the waste from getting compacted while it awaits incineration, and to drop it in the boilers — were upgraded in 2018 and 2019, along with the rails and festoon cables attached.

During the tour, Boiler 1 was undergoing the emissions control upgrades and Boiler 3 was down for maintenance. In addition to the fabric filters, the boilers were also outfitted with new advanced selective non-catalytic reduction (SNCR) systems. The systems work automatically (monitored by a WIN employee) to inject urea and lower nitrogen oxide emissions.

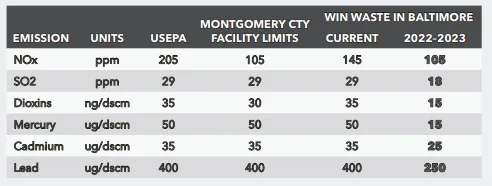

Under the terms of WIN’s 10-year waste contract with Baltimore City, NOx emissions are limited to 105 parts per million, compared to the facility’s previous performance of 145 ppm. Baltimore placed more stringent limits on other forms of pollutants in the 2020 deal as well, after passing but losing a court battle over its Clean Air Act that proposed limits beyond what WIN said it could reach.

Waste fed into the boilers goes from “trash to ash” in about an hour, said Travis Satiritz, corporate maintenance account manager with WIN. He said the facility reduces the waste volume by 90%, and the resulting bottom and fly ash are mixed together and go through a metal recovery process.

More than 12,000 tons of ferrous and non-ferrous metals are recovered from the ash annually, WIN says. The leftover ash, which WIN describes as “inert,” is sent to landfills.

The fabric filters are organized in a series of compartments in baghouses that trap emissions. Satiritz said the system was designed with a measure of redundancy to ensure that WIN can take out and replace the filters as needed without shutting down the facility. The bags are typically replaced on a two- to three-year rotating basis.

WIN Waste uses fabric filters at all but one of its 14 facilities, Satiritz said. But the combination of the SNCR system and modern baghouse system will make the Baltimore facility “one of the cleanest in the country,” he said.

The steam generated by the plant is sent through a 60 megawatt turbine, and a portion of that energy generation is used to completely power the plant. The rest of the energy is used by Baltimore City, with some steam used for heating large buildings. WIN says the total energy generated by the plant is enough to power more than 31,000 homes each year.

Upgrades to the facility were complete by mid-June, Satiritz said. All three boilers are now back online, and WIN is currently working to fine tune the facility