To combat plastic pollution’s environmental justice impacts, the U.S. must cut production of new plastics, support policies that hold producers accountable and better amplify perspectives of those whose lives are most impacted by pollution, former U.S. EPA official Carlton Waterhouse said during a panel discussion on Tuesday.

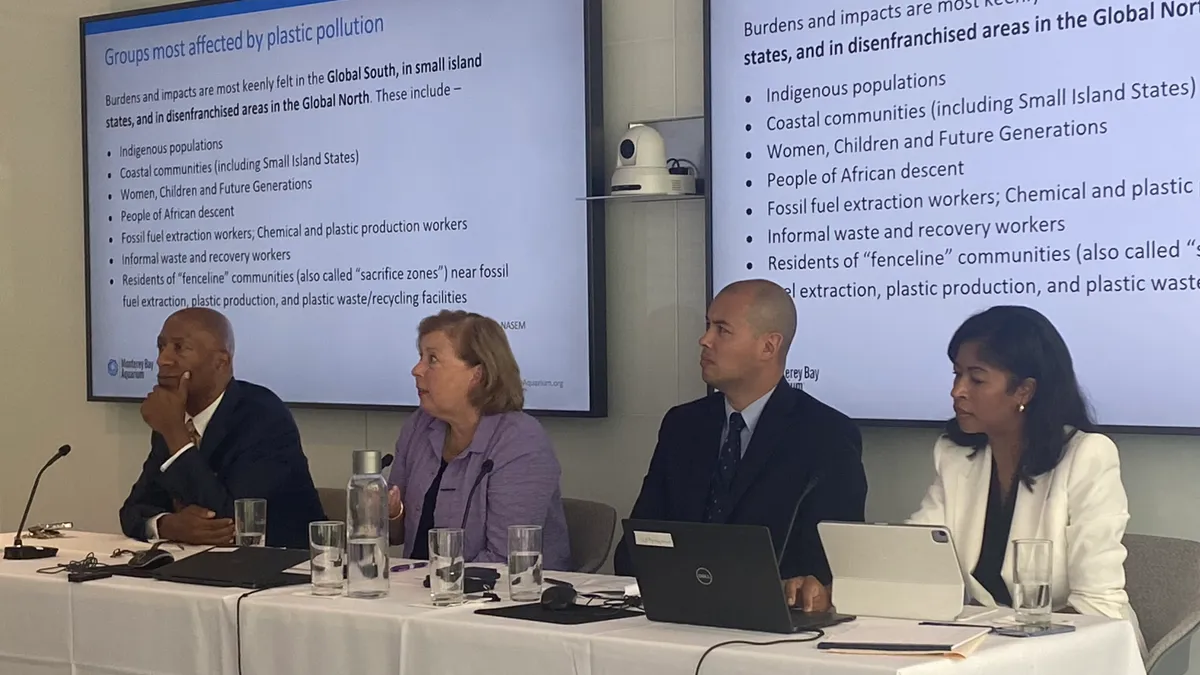

Waterhouse was among the speakers at the Environmental Law Institute’s “Moving Beyond Plastic” panel in Washington, D.C., which examined the disproportionate impact of plastic pollution on marginalized communities. Jonathan Black of the White House Council on Environmental Quality and Margaret Spring from the Monterey Bay Aquarium also discussed how the U.S. fits into global efforts to reduce plastic pollution on vulnerable communities.

Waterhouse, formerly the EPA’s deputy assistant administrator for the Office of Land and Emergency Management, is now a law professor at Howard University. He urged the White House and the EPA to prioritize strategies to reduce plastic production — a view he said he didn’t voice when he worked for the EPA because it “may or may not be consistent with the administration's position and negotiations. He believes it will help long-term plastic pollution prevention.

Waterhouse, whose nomination for an EPA assistant administrator role had been stuck in limbo for a year and a half, left the agency in February.

“The EPA says, reduce, reuse, recycle, right? Reducing and reusing are the first two priorities, and recycling is the third,” he said. “If we reduce, it means we have to go to the production of plastics. We have to be willing to see a reduction in production in order to make this a manageable problem right now.”

The conversation around the U.S. approach to plastic production and recycling has been a hot topic recently, causing tension between lawmakers and activists who want an end to new plastics and those who say some plastic bans are unrealistic and could harm the economy.

Waterhouse also acknowledged that environmental justice communities not only bear a disproportionate exposure to pollution from industries like plastic production, but they are also underrepresented as “beneficiaries of the profits from those corporations” because they’re less likely to be shareholders or board members of such companies.

“As we think about environmental justice, it’s important to not just think about who bears the pollution but who also carries the profits,” he said. “We're talking about industries that are very profitable … There's also a big resistance to change, because that change will impact that profitability.”

Waterhouse and other speakers touted extended producer responsibility legislation as one option for holding plastic producers more accountable for the materials they put into circulation. Spring, the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s chief conservation and science officer, cited California’s passage of SB 54 as an example of how a state can enact a comprehensive EPR bill that also encompasses environmental justice aspects because it calls for significant funding for marginalized communities.

Waterhouse said state and local legislative efforts will be critical to reducing plastic pollution. He urged lawmakers and those involved in crafting legislation to collaborate with other states that may have passed similar laws to share wisdom on hurdles and strategies.

Some states, including New Jersey, have also recently enacted environmental justice permitting laws that require a stricter evaluation of the environmental and public health impact on “overburdened communities” during certain permit expansion or renewal applications. Industries often are required to host community meetings with fenceline neighborhoods in such laws.

Waterhouse said those provisions are important, but don't fully address the wide range of cultural, religious, racial and social backgrounds that marginalized groups bring to the table.

“Just because you give that 30-day public notice that’s required by law doesn’t mean everyone who attends is actually going to have the same weight in what they say,” he said. “That means we have to lift up the voices of those members of those marginalized communities, and in some ways, giving them an outsized opportunity to be heard, because it requires that we listen more attentively than we might otherwise.”

Making meaningful changes based on community feedback will be an important part of the federal government’s ongoing efforts to curb plastic pollution, said Black, CEQ’s senior director for chemical safety and plastic pollution prevention. His and other federal agencies under the Biden administration are also working more closely to reduce overall plastic use, such as by phasing out single-use plastics in government buildings and other applications.

Black also urged the public to make comments on the EPA’s draft National Strategy to Prevent Plastic Pollution. The draft strategy calls for aligning collection, recycling and composting with environmental justice efforts, and the public comment period has been extended through July 31.

That draft strategy will also be part of the U.S. contribution to ongoing United Nations negotiations on a global treaty to end plastic waste. Spring said the legally-binding agreement will have major impacts for how the U.S. and other countries collaborate on future waste prevention and environmental justice work. “This was once just considered a waste treaty, but now it’s a human rights treaty,” she said.