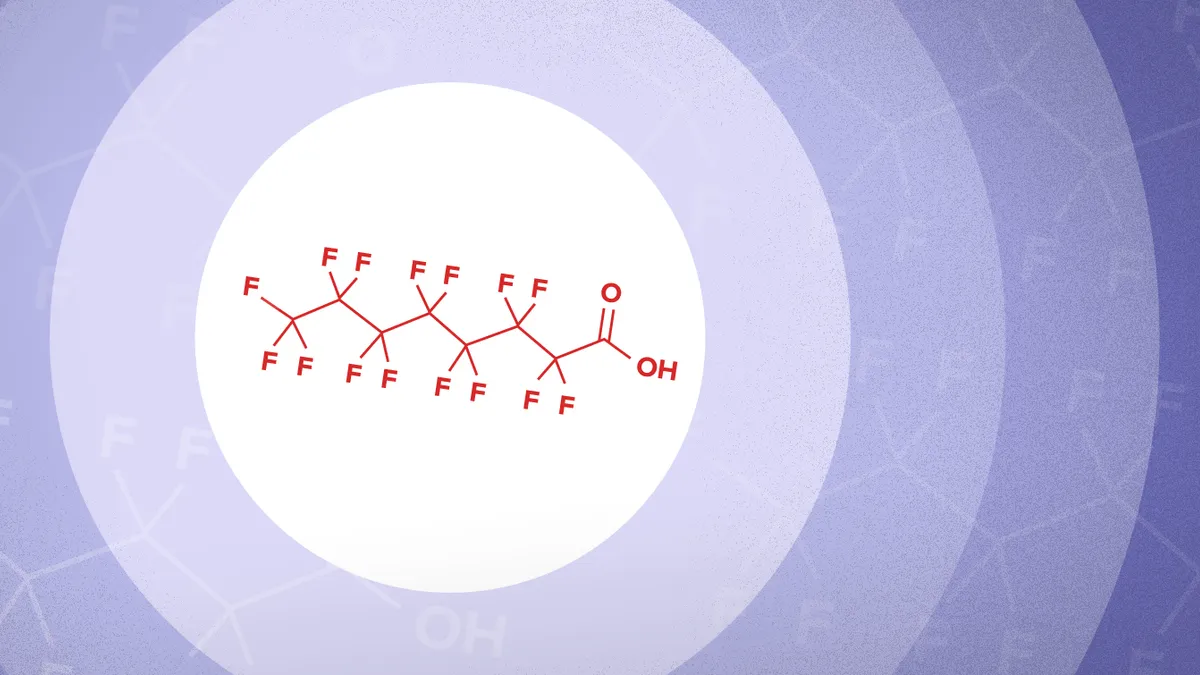

The U.S. EPA’s designation of two PFAS chemicals as hazardous substances under its Superfund law went into effect on July 8. The agency’s decision not to specifically exempt all facilities that receive but do not produce the chemicals, such as private waste and recycling facilities, has the industry searching for solutions.

On a recent be Waste Wise webinar discussing new regulations of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, industry group representatives said understanding of the flow of so-called “forever chemicals” is still in its infancy, as well as the best methods to neutralize products that contain PFAS.

They also expect to spend significantly on destruction or disposal technology, which could change the economics of disposal and even force some recyclers to begin charging to accept material, said David Wagger, chief scientist and director of environmental management at the Recycled Materials Association.

“Our industry, the profit margins are really tiny. If you have to add destruction technology to the PFAS you do extract, that might turn the whole proposition upside down,” Wagger said on the webinar. “It can change the nature of the industry just because the economics are so challenging.”

The EPA announced the change to the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act, or CERCLA, on April 19. Under the law, entities found responsible for contaminating a site with PFOA or PFOS will have to pay for cleanup. The decision made landfill owners, recyclers, composters and other stakeholders on the waste and recycling value chain nervous because it did not explicitly exempt privately owned facilities that are responsible for managing PFAS-containing products from liability.

Instead, the EPA released a companion “enforcement discretion” document indicating it would not focus enforcement on publicly owned or operated municipal solid waste landfills, instead targeting parties like manufacturers that have introduced significant levels of the regulated chemicals into the flow of commerce.

But that policy does not specifically mention privately owned or operated MSW landfills, further injecting uncertainty into EPA’s enforcement decisions, said Anne Germain, chief operating officer and senior vice president of technical and regulatory affairs for the National Waste & Recycling Association. She said that EPA has instead pointed private industry members to a separate section which notes “facilities that largely operate in the same purview as one of the discretionary enforcement categories would presumably be treated the same.”

“Unfortunately, discretionary enforcement is just that, it's discretionary. It might change,” Germain said. “Having that discretion upon discretion does not give us the warm fuzzies that they had intended.”

Kristyn Oldendorf, director of public policy at SWANA, noted her organization is continuing to work alongside others, including NWRA and ReMA, to push for legislative protection for so-called passive receivers of PFAS like landfills and recyclers. In the meantime, the amount of industry pilots already underway to begin testing treatment and disposal options is encouraging, she said. Such technologies include granular activated carbon, reverse osmosis and foam fractionation.

The EPA has made some federal funding available under the Safe Drinking Water Act for treatment technologies. It also released updated guidance on destruction and disposal technologies that specifically called out the potential of injection wells and thermal treatment technologies. But Oldendorf said that for the moment, the new restrictions are more like an “unfunded mandate” for most waste and recycling facilities, which will have to work out their own means of financing cleanup technology.

Doing so may mean passing on new fees to users. Germain noted landfills could upcharge customers for disposing of special waste if they have materials known to contain high levels of PFAS. But she said that the effects of new regulations on landfills will vary due to factors like access to deep well injection, leachate generation and facility size.

Oldendorf noted even setting a budget remains tricky, as landfills still expect the EPA to release additional guidance or regulation on leachate, another source of PFAS contamination into the environment. That will be especially challenging for municipalities, as they operate with strict financial controls.

“I think some of this will depend on what happens over the next few years,” Oldendorf said. “But certainly I think everyone is starting to think about it and hopefully starting to think about how to work it into their longer-term budgeting.”

Disclosure: The be Waste Wise webinar was moderated by Waste Dive Senior Reporter Megan Quinn.