Figuring out how to manage PFAS contamination has vexed government officials and industry professionals for years, but pending federal regulations and a wave of technology could start a new era of action against these forever chemicals.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances — long used in a range of products for non-stick and grease-resistant applications — are now known to cause serious health effects. The U.S. EPA is in the process of promulgating multiple regulations to address PFAS levels in water and waste streams, some of which have elicited liability concerns from solid waste facility operators who say they are passive receivers of PFAS-containing material.

Last week’s Northeast Conference on the Science of PFAS, hosted by the Northeast Waste Management Officials’ Association in Massachusetts, included updates from the EPA and others about how to study and manage this challenging class of chemicals.

Here are a few takeaways from sessions during the event’s first day.

Regulations are finally ramping up

After years of anticipation for PFAS regulations, 2024 is expected to be a key turning point.

One of the most foundational proposals, the EPA’s final drinking water standard, is imminent. The Office of Management and Budget completed its review of the measure on March 27, and observers expect it could be finalized by mid-May to avoid potentially being repealed by a future Congress under the Congressional Review Act.

“It’s going to come out soon,” said David Cash, EPA Region 1 administrator.

Anticipation for the proposed standard of 4 parts per trillion for PFOA and PFOS has led to investments of time and in technology that can be used at wastewater treatment facilities and other sites. Cash cited filtration technologies such as granulated activated carbon, reverse osmosis and ion exchange as examples.

“Because it's on the horizon, we know there's a huge amount of innovation and entrepreneurship that's going into solving some of these issues right now. And in our [regulations], we're not going to dictate technology, that's something we've left up to the utilities, states and municipalities. The rule is flexible on timing,” he said.

Cash, who is co-chair of the EPA’s PFAS Task Force, said in some cases states are also pushing their own standards and environmental officials often raise the issue of PFAS when he talks with them

John Beling, deputy commissioner for policy and planning at the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, said his agency will issue regulations “at least as stringent" once EPA’s final rule comes out.

The session also touched on potential hazards from applying biosolids, also known as sewage sludge, on farmland.

“We are in the process of rethinking this whole thing; unrestricted land application of substances that include PFAS probably isn't a good idea,” said Beling.

Adam Nordell, a campaign manager with nonprofit Defend Our Health, said his family’s farm in Maine was polluted by this practice. Maine has a program to acquire PFAS-contaminated farms for research purposes and has enacted strict restrictions on land application of biosolids. Nordell’s group is advocating for the next farm bill to include language from a federal bill that would provide financial assistance for affected farmers.

Science on landfill effects is evolving

Many landfills have some level of PFAS contamination due to receiving consumer and industrial products that contained the material, but the scientific community is still working to better understand the nuances of this issue.

Researchers in Washington state analyzed 32 types of PFAS from leachate at 17 landfills and found that 5:3 FTCA was the dominant type. This correlates to items such as carpeting, textiles and food packaging. They found evidence that some older landfills had lower PFAS levels. They also found that manufacturers’ efforts to phase out long-chain PFAS didn’t necessarily lead to an overall reduction of the forever chemicals, because they were replaced with short-chain PFAS.

Maine’s Department of Environmental Protection also worked with 25 landfills to take five leachate samples over a two-year period. It also found 5:3 FTCA to be the dominant type, but levels varied widely.

The agency has been studying effects on wastewater treatment plants that accept leachate, which accounts for an estimated 25% of the throughput at these sites in Maine.

“Landfills are definitely one source of PFAS loading to our wastewater treatment plants, but it's important to keep in mind it's not the only source,” said Michael O’Connor, a senior environmental hydrologist with the agency. “Treating just landfill leachate might not be a silver bullet, so to say, for decreasing loading at wastewater treatment plants.”

Researchers at the EPA are also working to assess the PFAS impacts of normal and elevated temperature leachate on WWTPs. Initial results showed that elevated temperature leachate had higher concentrations of PFAS, but that didn’t necessarily translate to significant effects for WWTP operations. The full results will be published in an upcoming study.

Destruction technology is evolving fast

While some facility operators are waiting for final regulations before investing in concentration and disposal technology, others are moving ahead and many tests are underway.

The EPA published interim guidance in 2020 on PFAS destruction options, with another update pending. It detailed multiple concentration and disposal methods. The U.S. Department of Defense, which has many PFAS-contaminated sites, published its own update on PFAS destruction last summer.

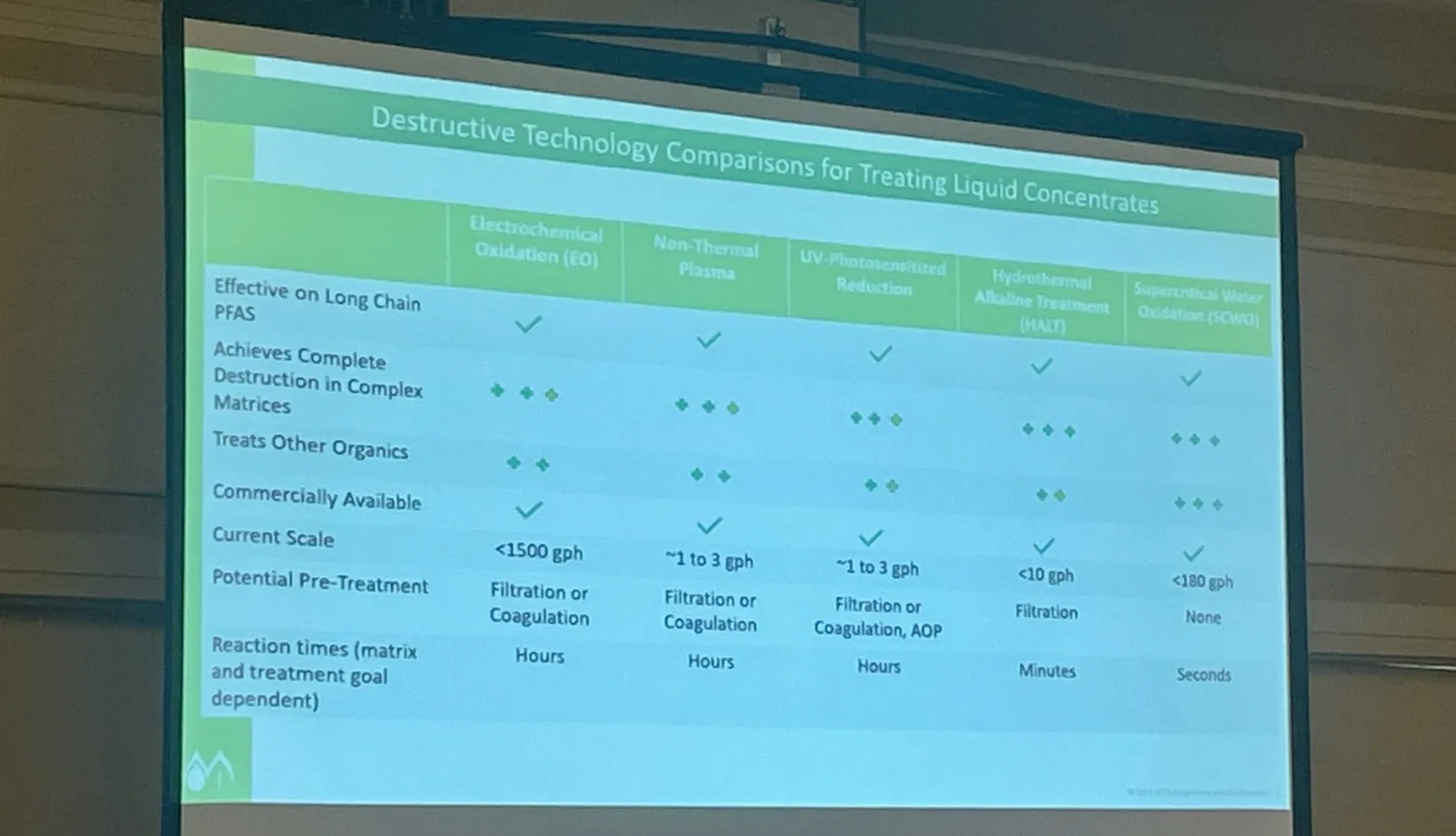

A subset of technologies is also emerging to destroy PFAS in leachate or other categories of material. Regardless of the final technology used, presenters said it’s important to pick the right concentration technology first.

“If you're looking to destroy PFAS, and to do it with one of these new technologies, it almost always makes sense to have that upfront concentration step,” said Steven Woodard, chief innovation officer at ECT2 (a Montrose Environmental company), noting this makes the technology more “practical and cost effective.”

Lauren March, a chemical engineer at consulting firm Arcadis, said that more dilute streams may be best suited for concentration via media-based solutions such as GAC or ion exchange, or membrane solutions like reverse osmosis and nanofiltration. However, foam fractionation may be better suited to landfill leachate due to its higher solids content.

Facility operators also have a growing number of choices that could be used to manage these concentrated streams. Some are better suited to certain streams. Operating costs, throughput and processing time are also important factors.

“The ambient destruction technologies are less capital intensive, because you're not heating and applying a lot of pressure. But they're also slower,” said Woodard. “As you move to [supercritical water oxidation] and [hydrothermal alkaline treatment] and higher temperature and pressure technologies, you achieve a higher degree of mineralization, and it's much faster. But it's also capital intensive and the conditions are more aggressive.”

All of this factors into the size, cost and operating logistics of which technology the operator of a landfill or other site may choose. Some technologies can be installed onsite, while others may be mobile and service multiple sites. Arcadis is working on a project with Clean Earth (a division of Enviri) and multiple companies to assess a hub-and-spoke concept.

“Instead of moving a system to various sites, and having to pay for those mobilization costs or purchasing a system outright, the idea is to ship wastes to a regional disposal facility that would have a destruction system on site,” said March.

Many questions still remain about the application of these technologies, but presenters were optimistic that they could help manage this challenging waste stream.

“Often people refer to [PFAS] as a forever chemical,” said John Xiong, a principal consultant at environmental consulting firm Haley & Aldrich. “But with all these destruction technologies, they are not forever anymore.”