After years of sending leachate from the Coventry landfill downstream to a municipal wastewater treatment plant in Vermont, Casella Waste Systems is building an on-site facility to treat its runoff. Amid rising public concern over PFAS and new or forthcoming regulations, an increasing number of landfill operators across the country are considering similar moves.

As evidence of the risks to human health and the environment continues to mount, Vermont regulators are adopting limits on five types of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, including PFOS and PFOA. New federal limits are also underway. In 2022, the U.S. EPA announced it would drastically decrease its federal advisory level for the two substances in drinking water from 70 parts per trillion, set in 2016, to 0.02 ppt for PFOS and 0.004 ppt for PFOA.

Casella’s progress toward building its own leachate treatment facility coincides with efforts to expand the Coventry site. Even before Vermont legislators passed a law in 2019 requiring new drinking water standards, the company began studying its options for removing PFAS from its leachate.

In a 2019 analysis commissioned by the company — which Casella touts as one of the first of its kind in the country — engineering firm Sanborn Head found PFAS in “an overwhelming number” of materials coming into the Coventry landfill, said Samuel Nicolai, Casella’s vice president of engineering and compliance.

Specifically, 95% of waste samples analyzed contained PFAS, ranging from 0.043 to 2,030 parts per billion, according to the report. While the analysis found that 99% of the PFAS stayed within the landfill, the rest ended up in the leachate.

“We were ahead of the regulations,” Nicolai said. “Our current efforts are to manage that last 1% of PFAS in the leachate so that you are basically 100% containing all of the PFAS that is being derived from these waste materials.”

The next year, a report by the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation found that discharge from the wastewater treatment plants in Montpelier and Newport — both of which processed landfill leachate — had higher PFAS concentrations than discharge from other plants in the state.

Concerns about PFAS were rising across the border as well. In 2021, Canadian officials found PFAS in an intake connected to Lake Memphremagog, the drinking water supply for 175,000 residents in southern Quebec. It’s unclear which side of the border the PFAS came from, but some suspect effluent from wastewater treatment plants in Vermont may be at least partly to blame.

Until recently, the Coventry landfill sent its leachate to the Newport wastewater treatment facility, which is located on a tributary of the lake. Under an agreement with state regulators, a Casella subsidiary now sends its leachate to the Montpelier facility, which discharges into the Winooski River, part of the Lake Champlain watershed. A permit issued by Vermont’s Agency of Natural Resources on Dec. 21 allows Casella to continue sending leachate to Montpelier while the company develops its pretreatment facility at the Coventry landfill.

Evolving regulatory landscape

Other states, including California, Michigan, New Jersey and Washington, are also taking steps to limit PFAS, which has prompted more landfills to look at treating the chemicals on-site. While publicly-owned wastewater treatment plants have historically treated leachate, some facilities either have halted that practice or are planning to stop accepting the waste because of PFAS concerns.

“It’s more of a state by state issue than it is a federal issue. And, quite honestly, states are way out ahead of the feds in terms of actually implementing regulations that impact the solid waste community,” said Kevin Torrens, national practice leader for landfill liquids at Brown and Caldwell, an environmental engineering and construction firm that specializes in wastewater infrastructure and treatment. “So the landfills, the solid waste facilities are under the gun.”

The issue presents a new challenge for the landfill industry, he added, with an increasing number of operators looking for solutions. “Before PFAS started to bubble up, we kind of had leachate management reasonably understood, and then here comes PFAS. It’s part of almost everything we do nowadays.”

While landfills represent a small source of PFAS compared to some other sources, such as military bases and airports, they are common and easily regulated ones. Effectively managing PFAS in leachate will become increasingly important — and potentially costly — as state and federal regulators crack down on these “forever chemicals.”

In September, EPA proposed designating PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances under the Superfund law. If finalized, the rule would require facilities to report PFOA and PFOS releases and allow EPA to require cleanup and recovery of cleanup costs.

“EPA anticipates that a final rule would encourage better waste management and treatment practices by facilities handling PFOA or PFOS,” the agency said at the time. In December, the agency also issued guidance for states on how to monitor and reduce PFAS in discharge from facilities with select permits before it reaches wastewater treatment facilities.

A persistent and debated problem

PFAS are difficult to contain and remediate for two primary reasons: their ubiquity and their longevity.

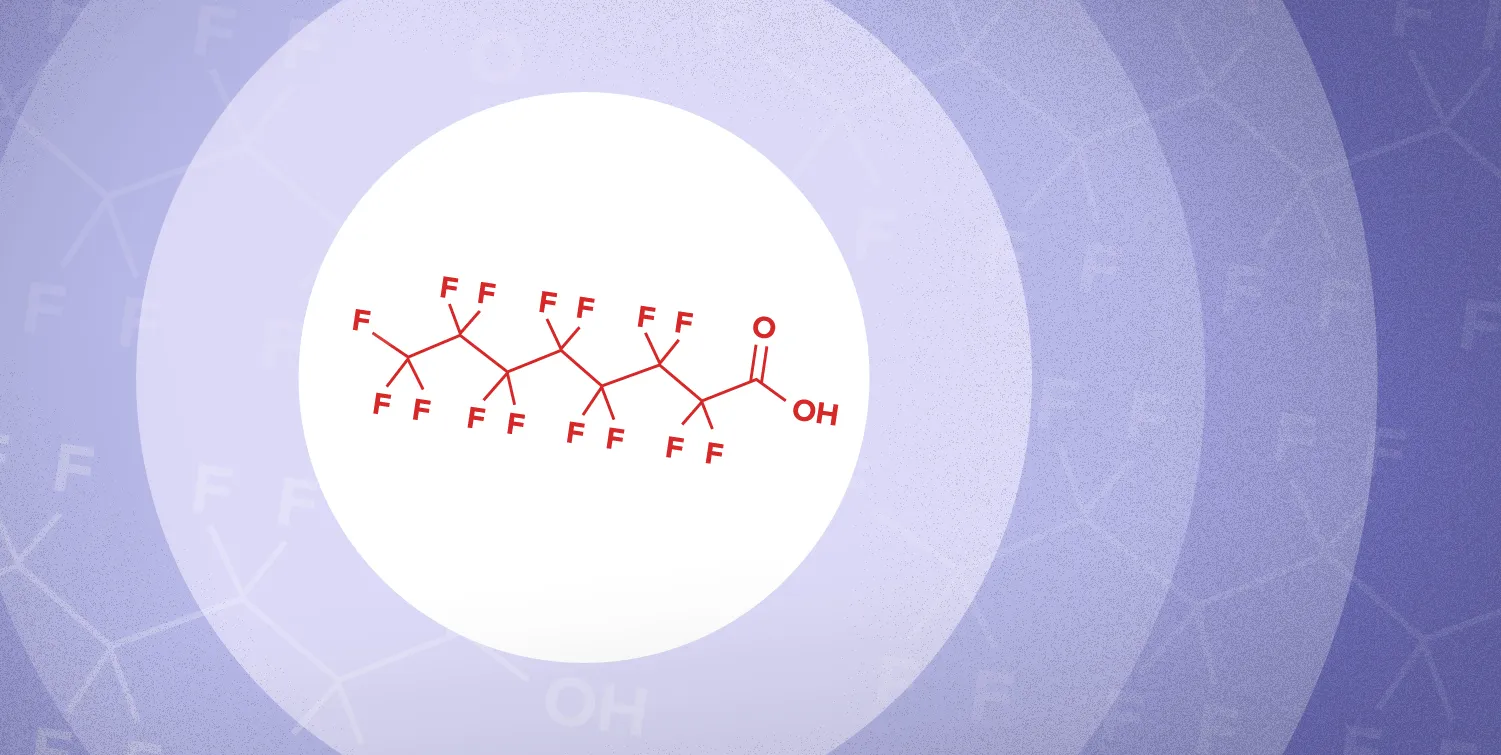

There are more than 5,000 of these compounds, and they are found in hundreds of products, including non-stick pans, pizza boxes, electronics, water-resistant clothing, cleaning products and some cosmetics. The tenacious carbon-fluorine bond — the strongest in chemistry — that defines PFAS means that the chemicals break down slowly. They can also accumulate in the air, water and soil, and in animals and humans over time, according to EPA.

Studies have found links between exposure to certain PFAS types and increased risk of some cancers. Other potential effects include suppression of the body’s immune system, reducing its ability to fight off infections, low birth weights in infants and delayed development and behavioral changes in children, as well as high blood pressure in pregnant women.

PFOA and PFOAS, two of the most widely used types of PFAS, were banned in the United States in the 2000s. But they still show up in imported goods and persist in the environment, as well as in closets and cupboards. When consumers throw away old goods containing PFAS, the chemicals end up in landfills where they can enter leachate.

“The challenge with PFAS is there’s a very broad range of contaminants in leachate,” Torrens said.

Typically, landfill leachate is treated at wastewater treatment plants. But conventional wastewater treatment methods can’t intercept PFAS and can even worsen the problem, putting more pressure on landfills to handle PFAS on-site.

During the wastewater treatment process, oxidation can convert compounds such as fluoroteloimer carboxylates into non-biodegradable perfluoroalkyl acids — a type of PFAS that is less studied than PFOA or PFOS, but highly toxic. Some research has found higher concentrations of PFAS in treated leachate than in its original form.

A February 2022 study in the journal Water Research about sources in Michigan found that concentrations of PFAS in effluent from all 10 wastewater treatment plants sampled were up to 19 times higher than levels in the wastewater entering the facilities. The same study, which analyzed 171 contaminated sites of various kinds, found that landfills were one of four main PFAS sources that accounted for 75% of the contamination. The other three were firefighting foams, metal platers, and automotive metal stamping facilities.

Given all of this evidence, waste industry operators are gearing up to make changes but also say they need more guidance.

“I think everybody sees regulation is coming and want to get ahead of it,” said Kurt Shaner, vice president for engineering and sustainability at Waste Connections, which has two on-site PFAS treatment facilities that came online in 2022. The company has increased the amount of leachate it processes on-site by 10% over the past two years. It plans to process at least 50% of leachate on-site by 2033, up from 37.1% today.

“The big challenge I think is just knowing what the goal is,” he said. “We have these options, but you can’t put them in place until you know what that is.”

In a joint letter submitted to the Senate environment and public works committee last May, the National Waste & Recycling Association and the Solid Waste Association of North America said that regulating PFAS waste under Superfund law could have unintended consequences, including raising the cost of managing the material and forcing landfills to restrict PFAS-containing waste.

The groups also said that since MSW landfills do not manufacture PFAS, they should not be held liable for PFAS contamination. Instead, the letter said, they can be “part of the long-term solution to managing these compounds.”

EPA said it received 60,000 public comments on the proposal and will publish responses to them soon. The draft rule is set to be issued within the next few weeks, with a final rule expected by the end of the year, EPA Deputy Press Secretary Khanya Brann said in an email. The agency is also crafting a rule to limit PFOA and PFOS in drinking water.

Emerging treatment methods

Since PFAS are so pervasive and complex, devising effective ways to remove the substances has proven difficult. But recent research and projects have yielded a few different methods for treating landfill leachate and drinking water.

The Coventry landfill is testing several of the most promising ones for its on-site facility. One is foam fractionation, which takes advantage of PFAS’s preference for the place where water meets air by using air bubbles to pluck PFAS out of water and reconfigure it into a foam. The PFAS is then condensed to concentrate the chemicals. The company is also looking at reverse osmosis, used for years at desalination plants, which has been shown to remove more than 90% of PFAS.

Another option is an electrochemical process that involves first separating out the PFAS using electrocoagulation, then breaking it down through electrooxidation. This method, essentially the chemical combustion of compounds in water, involves passing the PFAS-laden water by an array of electrodes. They trigger a complex chemical process that breaks down the PFAS molecules into shorter ones and eventually into carbon dioxide. In tests by Golder, an engineering firm based in Montreal, the method removed 100% of PFOS and 100% of PFOA. The company describes the the process as energy-efficient, cost-effective and scalable.

The Coventry facility will likely use more than one of these technologies in the final design, Nicolai said.

“We’re not selecting a technology that's only going to treat certain compounds or is only going to treat compounds down to a certain level,” Nicolai said. “We're aiming to try to get the levels in the leachate below laboratory detection limits, which are typically in that one to two ppt range. And we believe we will be successful at doing that.”

Each of these methods are likely to cost “several million” dollars.

“That's part of our evaluation as well, trying to figure out what the ultimate cost will be,” he said, adding that whatever the cost is will also be reflected in adjusted disposal pricing for customers.

The most commonly used technologies in the industry so far all have certain drawbacks. In reverse osmosis, for example, the membrane used to remove the chemicals is susceptible to fouling from other contaminants and requires disposal of the resulting PFAS-laden waste. Ion exchange resins are also frequently used but they require incineration of the resin, which can only be used once. Another method, which involves using a granular activated carbon filter, carries high operating costs because the filter needs to be replaced frequently. The used filters must be incinerated in an accredited facility to destroy the PFAS.

“Landfill leachate contains many other background constituents that will affect a given treatment process” said the EPA’s Brann in an email. “These other constituents are often at very high concentrations, and hence, will have a strong impact on the effectiveness of a given treatment process, along with other factors.”

All of these factors involved with on-site leachate treatment for PFAS using currently available technologies may make it cost-prohibitive for some landfills, according to the agency.

“For medium size and small size landfills, the volume of leachate generated is often too small to make PFAS treatment cost effective,” Brann said.

The ultimate goal is to develop a technology which can break down the strong carbon-fluorine bonds that make up PFAS, essentially destroying it rather than removing it. This is difficult to achieve, but two technologies — electrochemical oxidation and plasma — appear capable of it.

While these methods show promise, water officials and waste industry representatives say more research is needed on all PFAS to effectively regulate the substances — and develop the best treatment methods for them.

“Up to this point, most studies have focused solely on PFOA and PFOS, which leaves a severe data gap for the thousands of other PFAS compounds,” the Association of State Drinking Water Administrators said in a letter submitted to the EPA’s Office of Ground Water and Drinking Water in April 2022. “Robust information on health effects, analytical methods, and treatment efficacy are needed as we look to address additional PFAS in drinking water and other media.”

Despite the lingering questions around how to effectively contain PFAS, Nicolai says a proactive approach to managing the chemicals, which has included barring materials with high concentrations of them such as firefighting foam and contaminated soil from PFAS cleanups, has served Casella well.

“I think that early strategy helped us to really focus in on how do we best manage the remaining waste materials?” he said. “We’re coming now into the final steps of getting this treatment program installed, which we believe will provide the ultimate solution for us to manage PFAS.”