The U.S. EPA published a new list of chemicals last week that could be subject to Safe Drinking Water Act regulations in the next five years, including a “substantial expansion” to cover numerous PFAS chemicals.

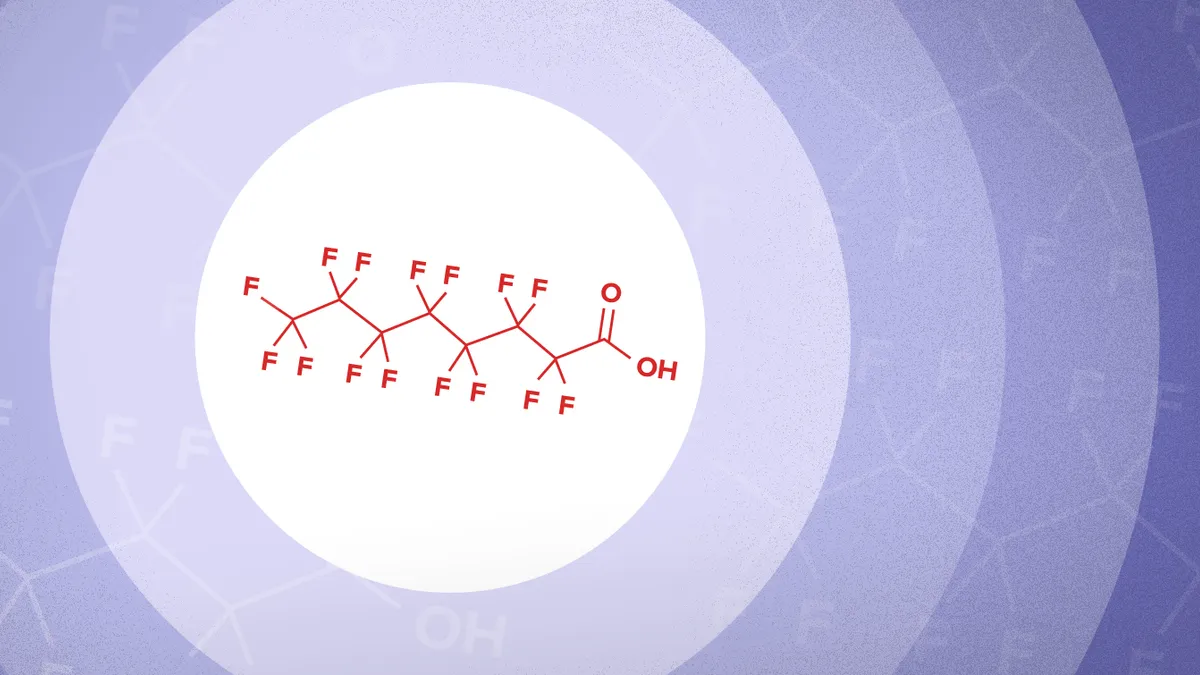

The list, known as the Final Fifth Drinking Water Contaminant Candidate List or CCL 5, lists per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances as a group rather than individually. Previously, the agency only listed individual PFAS for certain regulations. The CCL5 “looks further forward to consider additional protective steps for these forever chemicals,” said Radhika Fox, the EPA’s assistant administrator for water, in a statement.

The EPA still plans to propose national drinking water standards for two of the chemicals, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), later this year, she said.

The EPA also announced in August that it plans to label PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, commonly known as the Superfund law.

Waste companies are closely watching to see how these decisions might affect daily facility operations. Both the National Waste & Recycling Association and the Solid Waste Association of North America said future PFAS regulations, particularly the hazardous substance regulation, could be costly and ramp up liability concerns. The groups again called for the solid waste industry to be granted a narrow exemption from liability in a joint Nov. 7 news release.

The CCL 5’s mention of PFAS as a group of chemicals doesn’t guarantee it will regulate PFAS as a group under the Safe Drinking Water Act. The notice only covers PFAS “known to occur in drinking water and/or source water” and is not an exhaustive list, the agency said in the notice.

The EPA says it listed PFAS chemicals as a group in the CCL 5 rather than individually because future regulations could be too complex if considered one by one. Approaching the chemicals as a class will help the agency build “a strong foundation of science on PFAS while working to harmonize multiple statutory authorities to address the impacts of PFAS on public health and the environment,” the EPA said.

Over 4,000 PFAS may have been manufactured and used in numerous industries since the 1940s, the EPA said. Many of these products end up in landfills, leaving operator wondering how to manage them as they wait for future regulations.

Along with the PFAS chemical group, the new CCL 5 also lists 66 other individual chemicals, including chemicals considered cyanotoxins and disinfection byproducts. It also lists several bacteria and viruses.