One year after the U.S. EPA announced its strategic road map to address PFAS contamination, the agency is on track with some of its promises to further study and regulate PFAS, but more action is needed to quickly reduce human exposure, Environmental Working Group members said during a press briefing last week.

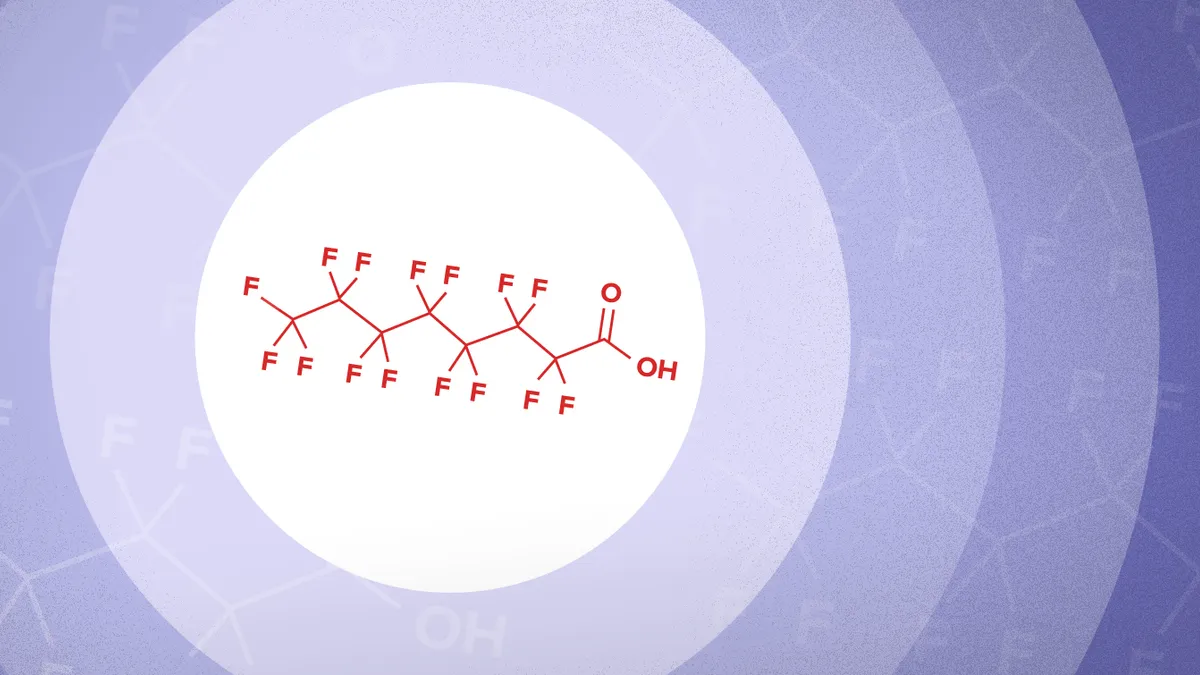

EWG recently published a report card keeping track of progress the EPA and other federal agencies have made to study, monitor and regulate per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, a family of numerous chemicals found in everything from outdoor gear to firefighting foam that have been linked to cancer and other illnesses.

A proposed rule setting enforceable limits on two PFAS chemicals, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), in drinking water should be coming from the EPA “any day now,” said Melanie Benesh, EWG vice president of government affairs, during the briefing. That major milestone will be the first time the EPA will name maximum contaminant limits for the two chemicals. The EPA plans to enact the final drinking water standard next fall, according to its road map.

The question for waste companies is how these decisions might affect daily facility operations down the line, especially since PFAS treatment and destruction technology is still scaling up and can be costly. Organizations such as the National Waste & Recycling Association and the Solid Waste Association of North America have said they are carefully monitoring any EPA actions around PFAS.

PFAS drinking water standards

The EPA already has announced drinking water health advisories for PFOA, PFOS, GenX chemicals and PFBS. This advisory is meant to provide information on what levels of exposure could cause adverse health effects. It is not an enforceable regulation, but “these health advisories showed that these chemicals are toxic at very low levels, and this is a really important step towards setting those maximum contaminant levels,” Benesh said.

The EPA will host a public webinar Nov. 2 about how it will develop the regulation and how to submit input on the proposed rule once it is published, but an agency representative said in an email that it does not plan to unveil the proposed regulation at that time.

The World Health Organization also published a draft guidance document last week on how it believes the EPA should handle the drinking water limits. The WHO called for the EPA to adopt limits of about 100 parts per trillion for either PFOA or PFOS in drinking water. Those levels are higher than the EPA’s guidance levels; the EPA’s health advisory estimates that amounts over 0.004 ppt for PFOA and 0.02 ppt for PFOS can be dangerous.

EWG, the American Chemistry Council and other stakeholders say they plan to weigh in on the EPA’s process before the proposed regulation is announced, Bloomberg reported, but it’s unclear how that feedback could influence the EPA drinking water announcement.

PFOS and PFOA hazardous substance designations

The expected drinking water actions follows the EPA’s announcement in August that it would designate PFOS and PFOA as hazardous substances under CERCLA Superfund law. One goal of such designation is to spur cleanup of industrial and waste sites said to have high concentrations of the chemicals.

The hazardous substances designation “will help kick-start the cleanup process of hundreds of communities devastated by PFAS harms, which are especially concerning for environmental justice communities, which are often disproportionately exposed to these chemicals,” Benesh said.

The Government Accountability Office has asked the EPA to conduct a more in-depth analysis of whether disadvantaged communities face disproportionate impacts from PFAS.

A recent study from researchers at Northeastern University identified more than 57,000 sites that are likely to be polluted with PFAS, researchers said.

Waste facility operators have concerns about what role they might play in the cleanup process. Both NWRA and SWANA have estimated the national costs to remove PFAS from landfill leachate are at least $966 million per year. In a May 10 letter to Congress, the groups voiced concerns that the designation of PFAS as hazardous substances could expose operators to liability if they cannot clean up “trace concentrations.” The letter asks Congress to grant MSW landfills a narrow exemption from liability.

The PFAS road map contains other major action items that could have an impact on the waste industry. The EPA plans to do more research and testing on hundreds of other PFAS, meaning it could deem other PFAS compounds as hazardous substances in the future.

The three-year road map action plan also sets a fall 2023 deadline to update federal research on the available methods for disposing of or destroying PFAS through landfills, thermal treatment and deep-well injection. This research will be important to the waste industry, which has explored numerous technologies to treat PFAS-containing leachate in recent years and could stand to benefit financially from being able to offer PFAS disposal services.

PFAS in biosolids and sewage sludge

A risk assessment for PFAS in biosolids is also expected to come from the EPA in winter 2024, and it also could have disposal impacts. This year, Maine became the first state to ban the use of processed sewage sludge as fertilizer due to concerns it spreads PFAS to crops and livestock. The new law could send more municipal sludge, which is sometimes used as fertilizer, to landfills in Maine or surrounding states, experts say. That could affect landfill capacity and complicate efforts to reduce PFAS entering landfills. Future EPA risk assessment information could also influence the flow of such sludge into landfills in the future.

The debate over how to manage PFAS in sewage sludge is playing out in Warren, Michigan, which uses an incinerator to process the material. Its city council recently voted against an incinerator upgrade project over concerns it would burn waste containing PFAS, local station WXYZ reported. The division head of wastewater treatment for the county said the incinerator upgrade would have destroyed 99% of PFAS in the material and that the process would be safer than applying the sludge to the land, which is the current process, the Macomb Daily reported.

Other entities are working to reduce PFAS exposure beyond the plans EPA outlines in its road map. California just passed a law that aims to quantify PFAS-containing materials sold in the state or brought into the state. Bill sponsors say the state needs “accurate and timely data” to help regulators, public agencies and waste and wastewater facility operators “expeditiously develop and implement best practices or set discharge limits that will protect human health and the environment.”

Activists have also called for the federal government to avoid purchasing items that could contain PFAS, said John Reeder, EWG’s vice president of federal affairs. Federal government procurements of goods and services total more than $600 billion a year, he said, and “steering those purchases away from PFAS- containing products can send a very important signal to the marketplace and create an incentive for companies to produce safer alternatives.”