Waste facility operators are strategizing how to update their PFAS management strategies in light of new final drinking water standards for several types of PFAS the U.S. EPA announced last week.

Waste companies said they are generally supportive of the new standards and efforts to improve drinking water nationally, even as they are working to understand how the regulations might impact operations at landfills. The rules are likely to affect how they approach leachate management and groundwater monitoring efforts as well as how they interact with wastewater treatment facilities, companies said.

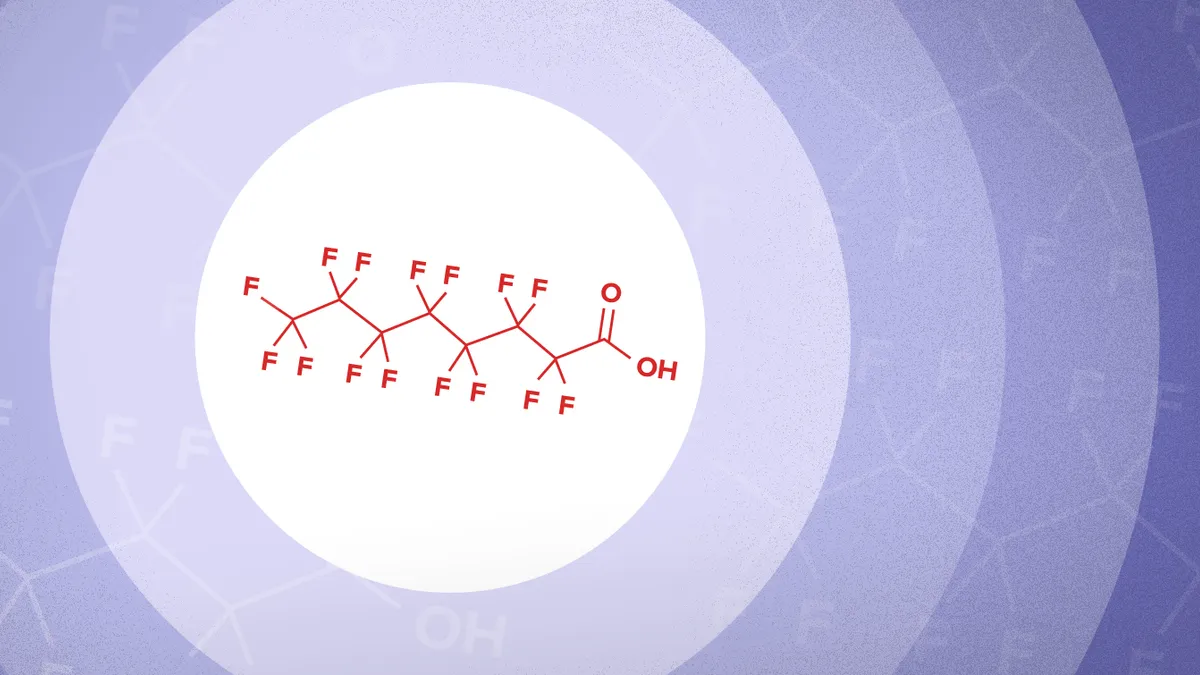

The standards are a major step in the EPA’s efforts to regulate the chemicals the agency says are dangerous to human health and the environment. They set an enforceable maximum contaminant level of 4 parts per trillion for PFOA and PFOS. The standards also set a non-enforceable maximum contaminant level goal of 0 ppt for PFOA and PFOS, a move meant to convey that no level of exposure is safe from potential health risks.

The rule further sets an enforceable MCL, and an MCL goal, of 10 ppt for PFNA, PFHxS and HFPO-DA, the last of which are also known as “GenX” chemicals. Additional limits were set for mixes of two or more of PFNA, PFHxS, PFBS and GenX.

Working with water treatment facilities

Top of mind for some companies is how the regulations could affect landfill operators’ relationships with wastewater treatment plants that treat landfill leachate.

The Solid Waste Association of North America expects the drinking water standards to put pressure on wastewater treatment plants to reduce or eliminate their effluent discharges to surface water bodies. That could mean those treatment plants then put pressure on landfills that send their leachate to those facilities for treatment.

“The new drinking water regulations have the potential to significantly disrupt the synergy that currently exists in the entire solid waste, water treatment, wastewater treatment, and biosolids management system upon which much of the country now depends,” said Jeremy O’Brien, director of applied research at SWANA.

The rule stipulates that public water systems must complete initial monitoring for certain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances within three years and implement solutions within five years if PFAS levels exceed the standard. The EPA estimates this could affect 6% to 10% of the 66,000 public drinking water systems in the U.S.

Amy Lestition Burke, SWANA’s CEO, said PFAS mitigation is a high priority for the organization’s members, who are “actively researching and investing in technology to remove PFAS and are committed to continuing to research and test solutions.”

Researching and investing in leachate treatment options

Many waste operators are already managing PFAS in leachate using various technologies, including several landfill companies that recently invested in building their own on-site wastewater treatment plants.

Operators in some states also must comply with state drinking water standards that mention PFAS. According to Safer States, 11 states have maximum contaminant levels for certain PFAS in drinking water, while numerous others have adopted health advisories or notification levels.

Jeff Weld, Casella’s director of communications, said its landfill in Coventry, Vermont, was one of the first facilities in the country to use a foam fractionation technology on site to remove certain PFAS compounds to levels required by Vermont’s state law.

The system can consistently remove more than 95% of four types of compounds and is working to consistently remove a fifth type, he said.

“While this method is not intended to treat leachate to EPA drinking water standards, it does significantly reduce the PFAS that are in leachate which is then sent to wastewater treatment facilities,” he said.

Several operators said they will be researching, testing and updating leachate treatment methods in light of the new drinking water standards. In an emailed statement, Republic Services said its Subtitle D landfills continue to work with its local public wastewater systems “to ensure compliance,” all while investing in leachate treatment methods such as reverse osmosis. Republic is also in the process of “piloting new technologies,” it said in the statement.

WM is also working “in conjunction with technical experts and academic institutions” to evaluate different techniques for treating and destroying PFAS in landfill leachate, the company said in a statement.

Landfill operators may look to the EPA’s updated disposal guidance, also announced last week, which offers research on what types of PFAS have been found in leachate and a range of technologies available to treat it.

Managing potential new costs and opportunities

Researching and adopting such PFAS treatment and destruction technologies will add capital costs and long-term operational expenses, along with costs to manage spent treatment medium, SWANA pointed out. “Existing detection and destruction technologies are currently very expensive and not all are scalable,” the association said in a statement. SWANA says it’s also concerned that the costs to treat drinking water could go up, which may impact the cost to treat leachate and other wastewater.

The EPA last week announced $1 billion in new funding for initial PFAS testing and treatment at both public water systems and private wells. It’s part of $9 billion in funding for addressing PFAS issues set out in the 2021 infrastructure law. Another $12 billion from the infrastructure law is meant to address overall drinking water improvements, which could include PFAS-related issues.

At the same time, some landfill operators see PFAS management as a potential business opportunity. Among those companies is Clean Harbors, which has grown its PFAS remediation line of business in recent years, and Republic Services, which says the 2022 acquisition of US Ecology has helped position it as a growing environmental services provider, including as a PFAS management provider.

At the same time, landfill operators say the best way to manage PFAS is for manufacturers to stop using the chemicals in products. “Ultimately, the solutions to eliminating them from society more likely exist at the beginning of the product life cycle rather than at the end of the waste stream, however we continue to do our part in protecting public health and the natural environment,” Weld said.

Many in the waste industry also consider landfill operators to be “passive receivers” of PFAS-containing material. The EPA is expected to soon designate certain PFAS as hazardous substances under Superfund, a move the waste industry said could unintentionally saddle operators with unfair costs and liability. It’s unclear when the EPA will make this designation.

Though unknowns remain, industry groups say they will continue to stay in communication with the EPA as they gain more clarity about the PFAS regulations’ impacts on business and operations.

“We want to be good partners with the EPA and with regulators, and we’ll continue to work with them closely into the future,” said Brandon Wright, NWRA’s vice president of communications and media relations.

Correction: A previous version of this story had an incorrect reference to the date Republic Services acquired US Ecology. That acquisition was in 2022.