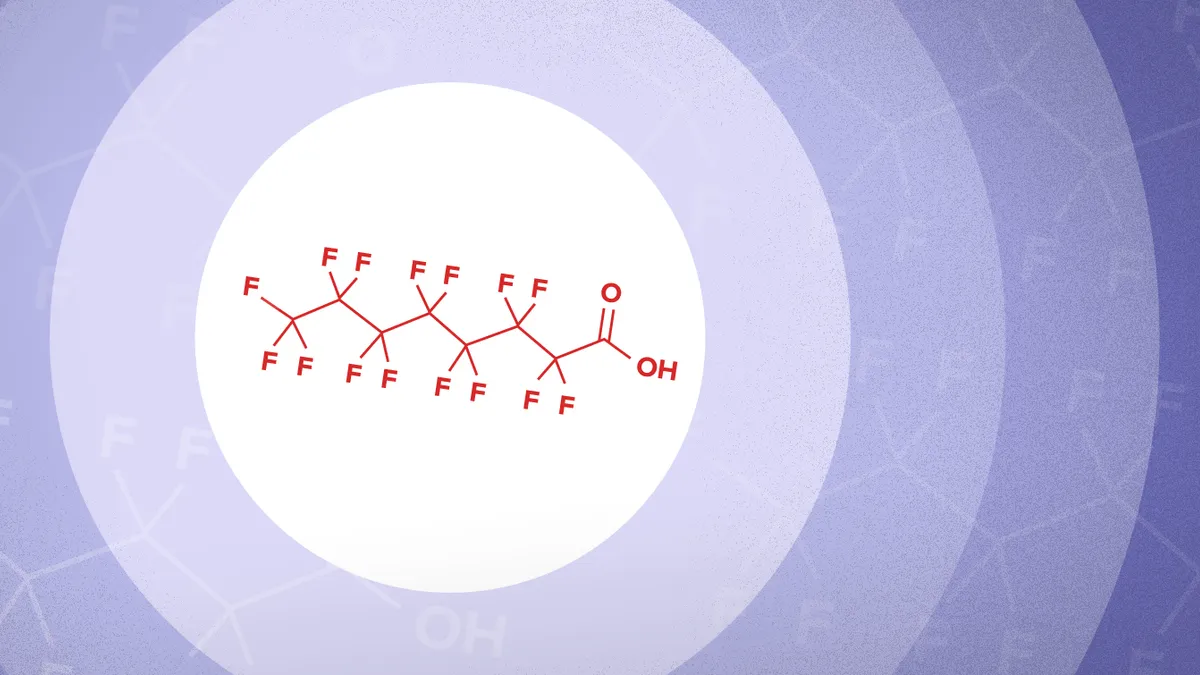

Now that the federal government has previewed new plans to regulate per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), sometimes known as “forever chemicals," landfill operators say they feel stuck between wanting more data and research before enacting future policy and needing clearer metrics to ensure safe PFAS management in the meantime.

The North American industry's largest publicly traded landfill operators, at a set of panel discussions this month, discussed how to best prepare for future federal PFAS regulations. The Biden administration is widely expected to designate PFAS as a hazardous substance and set enforceable limits for PFAS in the Safe Drinking Water Act – the first time the U.S. EPA would establish federal maximum contaminant levels (MCL) for PFAS chemicals. Some panelists wondered if regulators and the industry alike have enough information about PFAS in landfills to inform such long-term regulations.

“As an industry, we are seeing these regulations evolve quickly” at the federal level and even more quickly at the state level, said Joe Benco, director of engineering for Republic Services, at a Jan. 21 panel discussion hosted by the Environmental Research & Education Foundation (EREF). “But we’re not running a playbook because the science and the other pieces are still unfolding in front of our eyes.”

Some landfill operators predict that once the EPA sets more specific PFAS limits and regulations, they will need to monitor and track PFAS in more formal ways, such as through landfill leachate and gas sampling. Some are trying to plan ahead by preemptively collecting data on how and where PFAS appear in their facilities, especially in leachate, but most operators are in the “very early days” of such monitoring, said Jim Little, executive vice president of engineering and disposal at Waste Connections, during one of two panel discussions hosted by Jefferies on Jan. 14 and 15.

That’s partly because those steps are not currently required at the federal level, and there is no clear direction on what the EPA believes is the best methodology for detecting and sampling for PFAS in landfill leachate and gas samples, added Cindy Lin, a former regional water pollution coordinator and senior science and policy advisor for the EPA.

Preemptive monitoring could end up being more work than it’s worth, said Joy Grahek, executive vice president of strategic initiatives at GFL Environmental, during the Jefferies discussion. “It’s difficult to monitor when you don’t know what to monitor to. It’s a position we are all in, and it’s something to (look at) as we get more clarity around PFAS rules.”

A number of states, such as California and Washington, already regulate PFAS in drinking water through a MCL, screening level or action level. These metrics could be helpful guidelines for landfills wondering what future federal regulations could look like, Lin said.

Landfill operators looking for other clues of what might happen if the EPA names certain PFAS chemicals as hazardous substances can look to historical examples of how the EPA has treated other chemicals deemed hazardous in the past, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dibenzothiophene (DBT). These chemicals now fall under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, better known as Superfund, which make them subject to certain types of monitoring and cleanup requirements, Lin said.

Experts also noted that since PFAS is a class of thousands of chemicals it's unclear which ones will be prioritized. James Jones, former assistant administrator at the EPA’s Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention, said he is confident that two of those chemicals, PFOS and PFOA, "will become hazardous substances in the next two years, making them regulated contaminants."

Even as the industry makes predictions about future regulations, it is also eager for more detailed research that could better illustrate how PFAS shows up in landfills, as well as how effective modern treatment methods can be in destroying or sequestering PFAS, Little said.

The EPA recently released guidance on PFAS disposal and destruction, but stopped short of making policy recommendations or setting standards for such disposal. The document highlighted the science behind using deep well injection, landfilling and thermal treatment, ranking them in order of perceived safety and viability.

Anticipated PFAS regulations might also represent business opportunities over time, said Republic Chief Financial Officer Brian DelGhiaccio during the Jefferies panel. Handling other landfills’ leachate could be one potential avenue, he said. “When we look at (safety), waste handling, logistics, a lot of times, things that seem like threats or risk can be growth opportunities.”

During the same panel, Michael Battles, CFO of Clean Harbors, said it’s too early to put a price tag on what market opportunities PFAS management services could bring for his company, but he estimates it could be “very large.” Clean Harbors anticipates a potential 10 to 15-year window of opportunity on managing these chemicals once regulations are finalized.

Operators say they are confident their landfills, which are required to have specific liners and leachate systems to prevent groundwater contamination, are effective at capturing the majority of PFAS. EREF is currently working with the University of Virginia on a study examining to what extent, if any, PFAS might move through a modern liner system, said Bryan Staley, the nonprofit's president and CEO.

“Previous research suggests it would be unlikely, but we want the science available to document that, especially as more politicians get involved. Landfills came up rather frequently, so the science needs to be available for policymakers to aid in the discussion," he said.

Landfill operators don't know what types of PFAS-laden materials will come through their facility on a given day, so any landfill regulation policy discussions should also go hand in hand with long-term discussions about how to stop PFAS generation at the source, said Samuel Nicolai, president of engineering and compliance for Casella Waste Systems, during the EREF panel.

“When we talk about stopping PFAS, we need to start at [the] manufacturing level," he said. "There’s a voluntary ban on a couple compounds, and it’s not implemented widely. So more work needs to be done to stop it at the source.”