Many areas in California are working to scale up composting infrastructure as part of a state mandate to dramatically reduce organic waste disposal by 2025. The Napa Valley is decades ahead ahead, thanks to a high-value agricultural and vineyard economy.

Processing many tons of grape pomace — a residual material in the winemaking process — from vineyards in the valley was an early impetus for composting in the region. Today, while new operations have increased their activity far beyond just pomace, local participation in food scrap diversion is still relatively low, and some facilities are accepting organic waste from across the San Francisco Bay Area to fill their capacity.

Composting in wine country

One of the first ventures to develop composting infrastructure in the Napa Valley was Upper Valley Disposal & Recycling in St. Helena. Founder Bob Pestoni launched the venture in the late 1950s as an answer to the question many vineyards had of how to dispose of the many tons of grape pomace produced each harvest.

Pestoni had begun accepting food scraps several years earlier from across the Bay Area to feed the 600 hogs on his farm. In 1966, he signed his first contract with vineyard owner Robert Mondavi.

“Mr. Mondavi didn't want to dump the residual on the ground on his property,” said Christy Pestoni, the company’s chief operating officer. “And so he called my dad.”

It didn’t take long for word of this service to reach other vineyards and for the operation to expand beyond hogs, especially because, as Pestoni recalls, “the first year my dad fed [the grape pomace] to his pigs, he mixed it in with the swill that he was already feeding them and the pigs got drunk.”

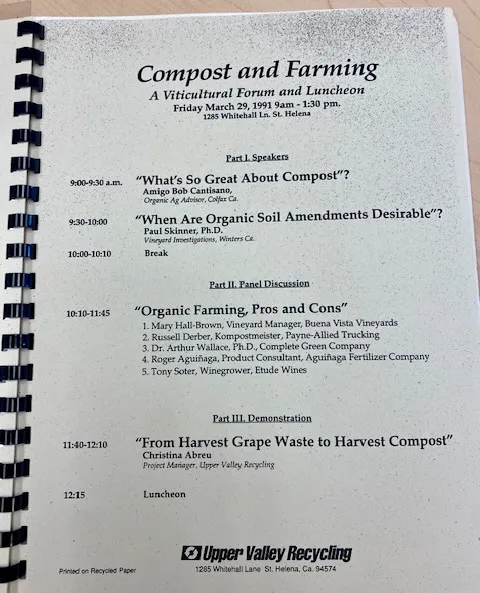

In the years to come, Upper Valley continued to invest in the science of composting, and has since been responsible for some of the earlier research to come out of California — as highlighted in a 1993 National Geographic spotlight on their operation.

The combination of wine and waste industry stakeholders resulted in a two-year “vinicultural forum,” including education efforts as well as compost use trials at Robert Mondavi Winery and Domaine Chandon over a three-year period. “We brought in soil scientists from the region and university experts from Italy to help educate farmers about the benefits compost use can have for soil, plant and fruit quality,” said Pestoni.

One of the earliest realizations Upper Valley made about its operations was the need to supplement compost piles, to balance out the grape pomace.

“When grape pomace is composted in a high percentage, the resulting compost is rather acidic,” explained Neil Edgar, a compost permitting consultant and executive director of the California Compost Coalition. Balancing the acidity required a source of carbon, which was found in rice hulls imported from farmers in Butte County, about 150 miles northeast.

Today, grape pomace still comprises around 60% of Upper Valley’s feedstock, which it acquires during the wine grape harvest season from August to the beginning of November. But as residential and commercial composting has taken hold in recent years, the company no longer needs to import carbon from across California.

Shifting market demands

In the last several decades, composting has expanded beyond the Upper Valley. The Napa Materials Diversion Facility, owned by the city of Napa and operated by Napa Recycling & Waste Services, is an industrial recycling and composting operation built in 1993 to meet the shifting needs of the region.

Since the early days of the wine boom over half a century ago, the valley has transformed from a sparsely settled agrarian region to a tourist destination now home to hundreds of wineries, commercial kitchens and an increasingly dense population. As a result, regional infrastructure has expanded to meet more diverse needs.

Today, the NRWS facility is permitted to handle up to 500 tons per day of organics. The majority is currently processed on site using a covered aerated static pile system, with additional material getting transferred to a new composting site in Yolo County. According to Tim Dewey-Mattia, recycling and public education manager at NRWS, only 7% or 8% of the feedstock at the municipality's facility in American Canyon consists of grape pomace. What that facility does receive is currently being sold for cattle feed as an alternative to grain, at a time when grain prices are high and the nutrient value is quite similar.

Dewey-Mattia said compost from operators in the Napa Valley might be pomace-heavy, or it might not — it all depends where (and also what time of year) you get it. Still, compost from municipalities in the Napa Valley continues to have a reputation of being overly rich in pomace, which hasn’t always been viewed positively by a new network of high-end culinary gardens that have popped up in recent years to accompany Michelin-star restaurants, like The French Laundry, that fear the acidity will adversely affect yield and crop quality.

“Initially, when I first moved to Napa and started farming here, I was advised against using the Napa compost by other local culinary gardeners and farmers,” said Rachel Kohn Obut, who runs the small-scale Little Moon Farm in Napa.

She tried purchasing boutique compost from a retailer in Sonoma County, but that quickly became “prohibitively expensive” for a small farm like hers, especially when compost produced municipally is much more affordable at around $13 per cubic yard. According to Dewey-Mattia, local farms and independent landscapers make up a small but not insignificant share of their end-market customers — around 5%.

"I've noticed it depends on what time of year it is," said Joey Pader of Soda Canyon Farm. In the early fall, just after the grape harvest, is when the pomace hits its peak. He also noted that compost facilities higher north, where the majority of vineyards are located, consistently have “way more” pomace than seen at the City of Napa’s facility, which is located farther down Highway 29 — making it much more connected to the rest of the Bay Area and a gateway to wine country.

Both Kohn and Pader say the criticisms of quality have not been borne out by real world evidence. “Some farmers had concerns about the acidity of the pomace,” said Edgar, but most adopt “a more practical view.”

“You’re not putting so much compost on the ground that you’re really going to affect the quality of the soil to a large degree,” so end markets have never really been an issue, he said. “The inherent soil conditions and microbes are going to neutralize that in a rapid time frame anyway.”

Looking ahead

In general, the diversity that measures like the SB 1383 organics recycling law brings to their feedstock has been a bit of a blessing, according to both Dewey-Mattia and Pestoni. The higher volume of food scraps balances out another source of feedstock that has ramped up in the last few years: landscaping materials and debris from wildfires, as well as from people doing defensible clearing work on their properties.

But when it comes to increasing food scraps in the waste stream, the biggest obstacle is participation, said Pestoni. “Not everybody's doing it, we're probably seeing about 2.5% feedstock in the household as food scraps. So not much.”

That number is higher for the Napa facility, around 10% since the implementation of SB 1383, said Dewey-Mattia. That is largely because the areas they serve, like the city of Napa, are more dense — but it’s still not what it could be.

“We've started doing studies looking at what's in people's bins and fewer than half of the residents are actually participating in food composting,” he said. Currently, the bins are mostly being used for disposing yard waste. Dewey-Mattia estimates there’s about 20,000 tons of food waste per year they are missing out on this way.

Currently, the lack of participation enables Napa’s composting site to accept imports of feedstock from other parts of the Bay Area, like Alameda County, and South San Francisco — which has its own benefits, since the percentage of food scraps (and the nutrients they contain) tends to be much higher. However, if the volume of locally-sourced material continues to grow, these areas would have to find other avenues to dispose of their material — something that Edgar said could be a challenge moving forward.

“Other jurisdictions are now 30 years behind at least from where Napa and Sonoma are,” he said, noting that there is a lot of impetus to continue developing infrastructure given support from the vineyards and the expanded organics collection mandate.

“There’s a lot of places now ramping up these new programs for SB 1383 organics recovery and they don’t have the processing infrastructure. A lot of those places don’t even think it’s possible,” he explained. “Napa and Sonoma are great role models, but it’ll take a little while to build that kind of a robust circular economy around organics.”