As U.S. cities pursue climate action plans to divert more waste from disposal and cut emissions, municipally-supported composting is growing in some parts of the country.

City employees and private partners in Los Angeles, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. shared their best practices and solutions to roadblocks in leveraging parklands for composting programs at a U.S. Composting Council (USCC) event last week.

With expertise in urban agriculture, parks and sustainability, panelists’ common threads included the need for public-private partnerships, community education and empowerment, and balanced distribution of responsibility.

Washington, D.C.

Josh Singer, community garden specialist in D.C.’s Department of Parks and Recreation, shared details on the agency's Community Compost Cooperative Network. Since launching in 2015, it now has 57 compost co-op sites across the city (49 of which are operational), with about 1,000 active participants. Those sites process around 29 tons of food and garden waste a month, or 348 tons annually.

In terms of co-op management structure, the goal is for a site to sustain itself without too much city support. A site is supposed to be started with a manager who trains future members and ensures quality control. Members, meanwhile, undergo a brief training and are meant to help process compost one hour per month. Singer said co-op culture and standards can decrease over time, and some sites have trouble getting members to show up on work days. For members who have not been actively engaged, Singer said D.C. co-ops learned to sometimes change lock combinations for sites to avoid an imbalance of material versus people to manage it.

Singer also said that basic steps like regaining community trust are key, noting that not all communities support and trust composting, due to past issues with rats or odors. “A lot of this was winning the community back over,” Singer said, noting that it’s key a community is on board before embarking on a project.

Additionally, it was previously difficult to track who was doing what at a given co-op site. To address that challenge, in 2019 D.C. began piloting an app designed to track the volume of material being composted at sites, plus allow for personal and site-specific rankings as to top individuals participating. COVID-19 budget constraints froze that contract, but D.C. hopes to continue it and Singer believes the technology is applicable to other cities.

Philadelphia

Following a longstanding example of composting at Philadelphia's decades-old Fairmount Park Organic Recycling Center, used almost entirely for non-food material, the city recently started pursuing an initiative to process food scraps from Philadelphia Parks & Recreation (PPR) centers. The resulting compost will used by the department and the FarmPhilly youth education program.

Through a request for proposals, the city selected area company Bennett Compost to service the operation beginning in 2020. The idea is for the city to provide resources to a local business while saving costs on collection and disposal, said panelist Daniel Lawson, PPR's sustainability and quality control manager. The arrangement lines Bennett up to add 20 to 30 rec centers each year, with up to 156 sites in year five. In general, public-private partnerships are a key tool, Philadelphia staff described.

As for the recently established Philadelphia Community Composting Network, there is a learning curve in initiating a program that is city-funded and community-led and getting everyone on the same page, noted panelist Ash Richards, the city’s director of urban agriculture. In the process of expanding composting, each site requires an operating plan. They described that training and site preparation phase proves to be the most resource intensive.

Los Angeles

Michael Martinez, founder and executive director of private company LA Compost, echoed the importance of collaborations. “It is all about partnerships," he said. "Every one of our sites has a partner," whether it's a school, a church, or a community garden, for example.

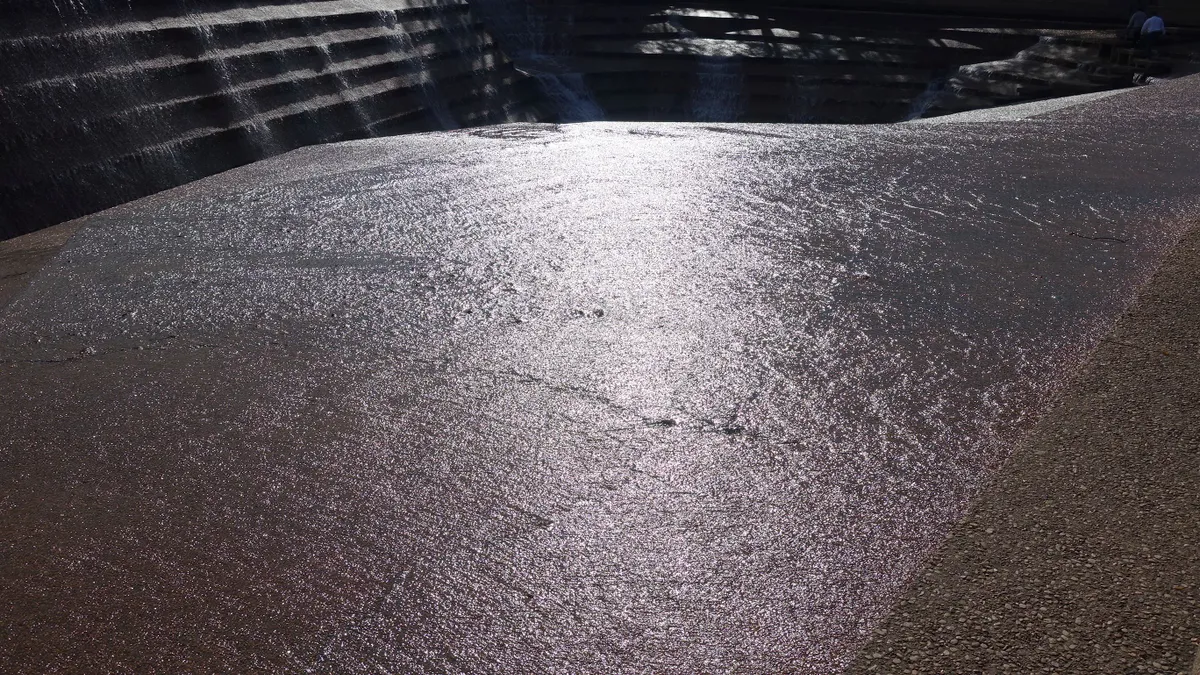

Following other cities such as New York and D.C., LA began a farmers market food waste drop-off program in 2018, which enabled scraps to go to a park less than two miles away for processing. That program was called out in LA’s Green New Deal plan published in 2019, which set a 2021 milestone of establishing food scraps drop-off locations at all city farmers markets, with the additional idea to partner with organizations for local composting.

Composting also received a boost in the city last September with the announcement of RegenerateLA, Martinez noted, a program to use the city's food waste to regenerate parklands with carbon-sequestering soil.

Still, composting advocates’ ability to utilize park spaces remains constrained by funding or, in some cases, city support. The USCC event comes as multiple local operations in New York City fight to retain their ability to operate on park land. When asked to respond to New York City leaders jeopardizing compost sites on park land, Martinez said, “Read the room. Look at what’s happening across the country because of the precedents that New York did."

"It would just be such a shame to be on this wrong side of history for climate change, carbon sequestration, food security, soil health, seeing ourselves as nature and parks being our natural spaces that elevate that," Martinez elaborated.