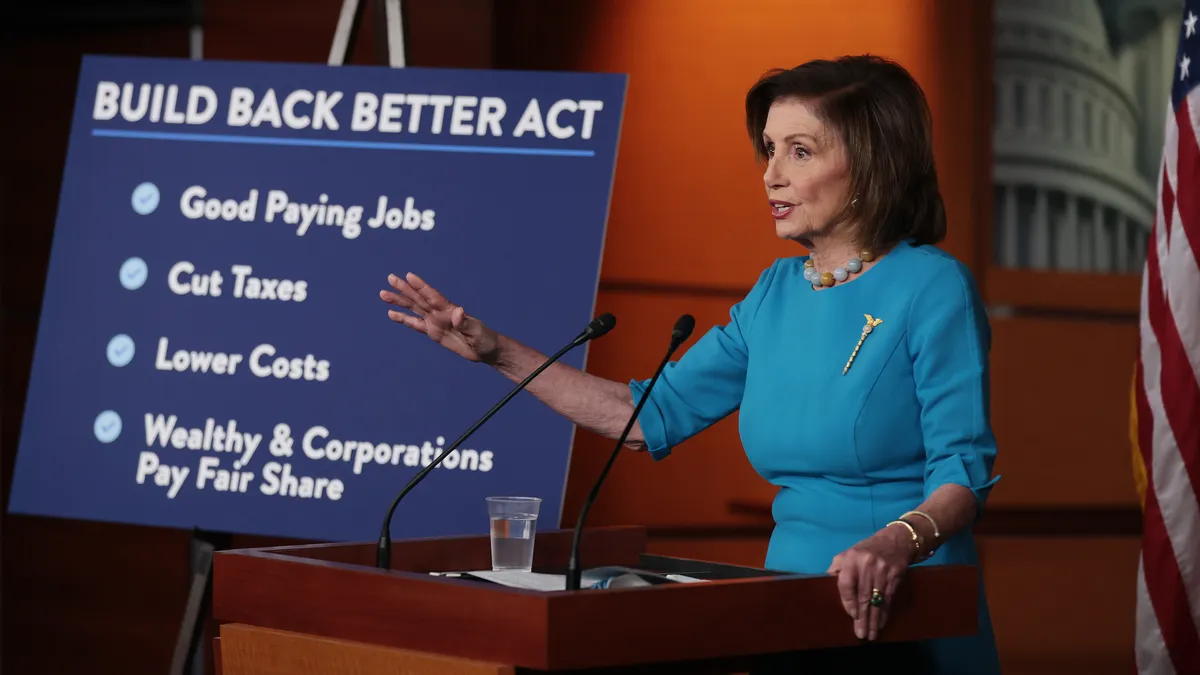

The $2 trillion Build Back Better legislation passed by the House two weeks ago is a much scaled-back version of President Biden’s original plan to pour money into fighting climate change and help families with paid leave, universal preschool and affordable health care. But it nevertheless will require chief financial officers, if it ends up passing the Senate in anything close to the same form, to think hard about their taxes, especially if their company operates globally.

The biggest hit, at least for the largest U.S. companies, is the minimum 15% tax on book income, which is expected to have an outsized impact on the way companies structure their performance-based compensation.

Although CFOs can consider it a win that the bill doesn’t include an increase in the 21% corporate tax rate — Biden early in his presidency was talking about raising it to 28% — the 15% minimum tax will complicate tax planning because of the way it’s pegged to book income — that is, companies’ adjusted financial statement income.

For many companies, one of the biggest drivers of differences between their book income and taxable income is their use of equity compensation — either stock options or restricted stock units — to help keep employee and company interests aligned.

When they’re calculating their book income, companies typically deduct the value of stock compensation at the time it’s granted to their employees, but when they’re calculating taxable income, the value isn’t deducted until the stock options are exercised or, in the case of restricted stock units, when the employee is vested.

As much as a third of the difference between book and taxable income stems from the treatment of stock-based compensation, the Congressional Research Service has estimated. That means the 15% minimum tax on book income amounts to a kind of penalty on stock-based compensation, the Tax Foundation says.

That wouldn’t just hurt the C-suite; the lion’s share of stock-based compensation — maybe as much as 78% — goes to non-executive employees, according to a National Bureau of Economic Research estimate. Technology companies are especially likely to give employees stock compensation as a part of their pay.

The good news is the 15% tax applies only to the biggest companies, those earning an average of $1 billion a year in book income over a three-year period, or, if they’re a subsidiary of a foreign company, $100 million in book income in a year.

Just looking at the $1 billion threshold, the tax is expected to apply only to a little more than 200 companies, The Wall Street Journal estimates. But, once it’s in place, it could become a mechanism that’s adjusted downward by a future Congress if it’s seen to be an effective policy tool.

Stock buyback tax

Another big hit could come from a 1% excise tax on stock repurchases by publicly traded companies. This is a scaled-down version of a 2% tax included in Senate legislation earlier this year.

The tax is intended to give companies an incentive to plow money back into productive investment like opening a plant or giving employees a raise rather than increasing the value of investors’ stock by decreasing equity dilution.

“It’s past time Wall Street paid its fair share and reinvested more of that capital into the workers and communities who make those profits possible,” Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) said when he co-sponsored the buyback tax bill in September.

Giving companies a productivity incentive might be lawmakers’ intention but the tax is unlikely to generate more investment because companies are already maxing out what they can spend, CFOs say.

Hormel Foods, for example, had to scale back plans for a new plant earlier this year because the shortage in silicon chips reduced the number of tools it could buy to outfit the facility, the company’s CFO, Jim Sheehan, told The Wall Street Journal.

The talent shortage is a productivity restraint, too. “There [are] only so many projects that we can take on,” Dave Denton, CFO of home-goods store Lowes, said.

These kinds of restraints mean Congress may be unlikely to see much change in corporate behavior as a result of the tax.

Global tax changes

For companies operating globally, the bill includes several changes that will increase the complexity of tax planning as part of an effort to get companies to reshore more of their operations and curb their use of low-tax countries to shield income.

Among other things, the foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) deduction would drop from 37.5% to 24.8% and the global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) deduction would drop from 50% to 28.5%. As a result, the effective rates for FDII and GILTI, once the 21% corporate tax rate is factored in, would be 15.8% and 15%, respectively.

In addition, to discourage companies from offshoring factories and to keep R&D in the U.S., the bill would let companies factor in the FDII deduction when they’re calculating their net operating loss deduction.

The bill would also require companies to apply GILTI on a country-by-country basis, which is intended to prevent companies from offsetting GILTI amounts between high-tax and low-tax countries — to prevent them from shielding income in overseas tax havens, in other words.

Another provision, also intended to keep companies investing in the U.S., would make gradual increases in the base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT) law. The tax would increase from 10% to 12.5% in 2023, then to 15% in 2024 and then to 18% after 2024. The tax wouldn’t apply to companies paying a foreign tax rate of at least 15% or, after 2024, 18%.

“We’re going to reward companies that invest in the United States,” Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), chair of the Joint Committee on Taxation, has said of the tax.

Bill prospects

It’s not clear when a companion bill will be taken up in the Senate, but, when it is, it will almost certainly be friendlier to companies than the House bill, analysts believe, given the outsized role of moderate Democrats Joe Manchin (W. Va.) and Kyrsten Sinema (Ariz.).

Even so, the direction of Congress on corporate tax policy seems clear. CFOs can expect to face far more hurdles, especially if they have global operations, to keep their taxes at or near where they are now.