When it comes to landfills, there’s the good, the bad, and the ugly.

The ugly is obvious: piles of old, rotting trash that don't smell too pleasant to local residents or landfill workers.

Then there's the bad, which gets many headlines:

- In Alabama, residents around the Arrowhead Landfill near Uniontown and the Stone’s Throw Landfill in Tallassee have alleged health problems and civil rights violations connected with the permitting of the landfills.

- In Virginia, Chesterfield County residents expressed concern at a public hearing about the planned expansion of the landfill into a nearby quarry, citing worries about odor control, ground pollution, and toxins.

- In Pennsylvania, the state Department of Environmental Protection fined Waste Management Inc. $500,000 for failing to contain odors at the Tullytown Landfill in Bucks County, PA, which drew complaints from residents across the Delaware River in Florence, NJ.

- In Ohio, Rumpke Waste & Recycling and Colerain Township have gone to court over the company’s request to expand its sanitary landfill eastward by 206 acres.

So, what’s the good news?

For starters, the persistent idea that the United States is running out of landfill space seems to be a false notion.

The National Waste & Recycling Association’s Begin With the Bin FAQ states, "On a national level, the United States has 20 years of disposal capacity."

David Biderman, executive director and CEO of the Solid Waste Association of North America (SWANA), agrees. "I don’t think we will face a national or even regional landfill disposal crisis in our lifetime," he said.

The fear that landfills may soon reach capacity began in the 1980s when the media began reporting about landfill shortages. In 1987, New York was estimated to have nine years of capacity left.

However, it wasn’t landfill capacity that was declining — it was the total number of active landfills. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reported that the number of municipal solid waste landfills has declined from about 8,000 in 1988 to 1,908 in 2013.

Small, local dumps closed when the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976 required they be lined to protect groundwater. In response, larger regional sanitary landfills that could accept waste from many municipalities — even from other states — opened.

"The change in the number of landfills and the increased size has led to more waste crossing state lines," said Biderman. "We're at the point where nearly every state in the U.S. imports and exports waste. The landfill industry has safely evolved to be able to satisfy that need."

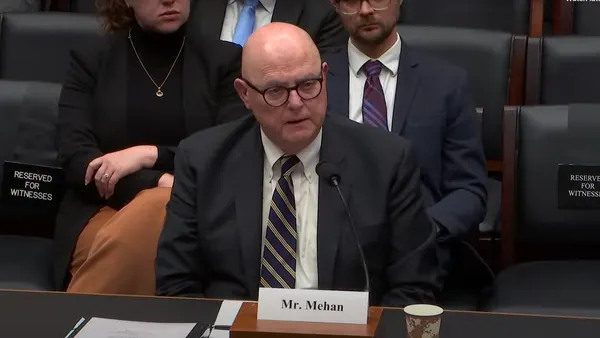

Not everyone sees it that way. U.S. Sen. Bob Casey, D-PA, has introduced the Trash Reduction and Sensible Handling (TRASH) Act of 2015 to restrict the flow of out-of-state waste into Pennsylvania, and give all 50 states more control over importing trash. It would also allow states to impose higher fees on out-of-state waste.

"Pennsylvania shouldn’t be a dumping ground for trash from other states," Casey said.

Biderman acknowledges the "hostility to waste generated in other places," and notes: "Trash generated in one state is pretty much identical to the waste generated in other places."

The route that trash takes to reach a landfill also gets attention. Residential waste from New York's boroughs of Queens and Manhattan are now making their way into Delaware before reaching their final destination in Chester, PA.

Wherever it comes from, when the trash gets to the landfill, waste management companies are finding new ways to reuse the waste or leachate. In many places, it's being turned into energy.

Some people are even finding landfills to be good neighbors.

At a public hearing in Pennsylvania to discuss the Lancaster County Solid Waste Management Authority’s $56 million plan to raise the height of the Frey Farm Landfill by 50 feet, resident Nancy Smith said, "We couldn't ask for a nicer neighbor. It's a beautiful landfill."

John Cox, a neighbor to the Frey Farm Landfill, added, "Nobody wants a landfill. Everyone needs one."

For that reason, Biderman said, "Landfills need to continue to be good neighbors."

"Landfills are essential parts of our national infrastructure," he added. "It's essential that they operate properly to protect health and the environment."