Electronics recyclers want to break open devices — and think consumers should be able to do the same.

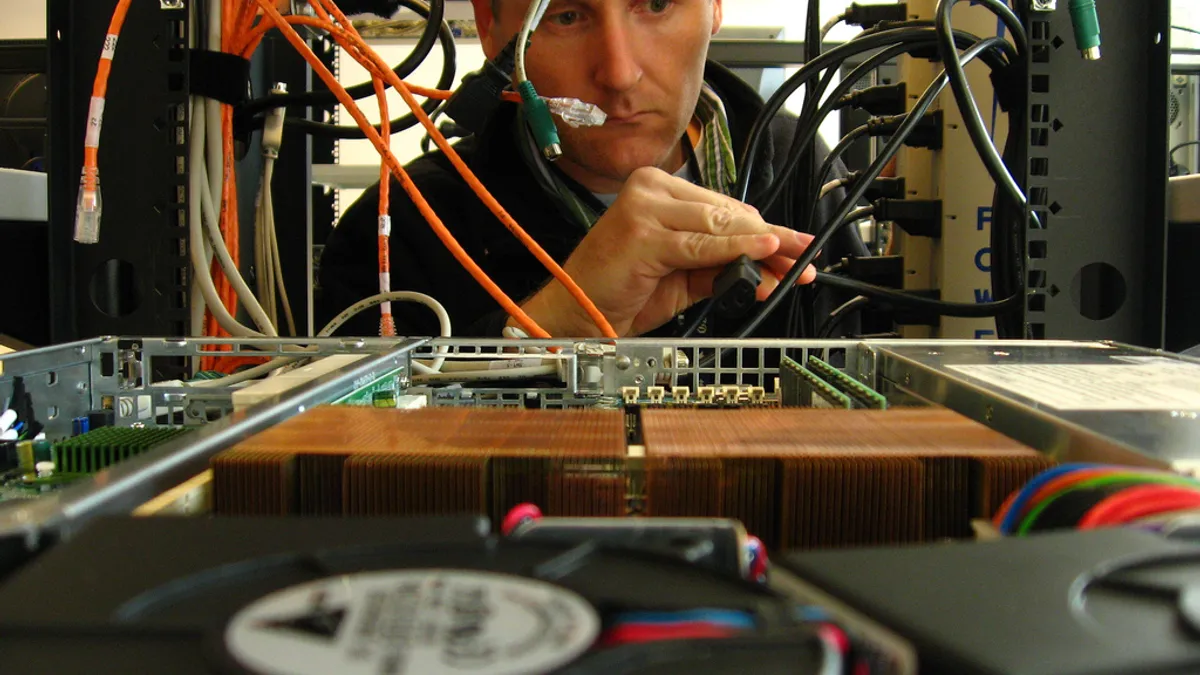

What was once the focus of reuse advocates and the tech community, the right to repair electronic devices has recently become a priority for the recycling industry, too. As new devices get smaller and more complex they’re also becoming harder to process cost-effectively.

While legislation has been proposed in multiple states to require manufacturers to release the schematics and tools for their products, those manufacturers seem to have little interest in letting this happen.

"When there's no competition for repair, guess what manufacturers do? They price their repair to be a reason to buy a new one," said Gay Gordon-Byrne, executive director of The Repair Association. "It's not nefarious, it's just obvious."

The Repair Association is the leading advocacy organization behind this issue and has been working to make it easier for devices to be repaired rather than discarded. Repairing electronic devices and appliances wasn't always simple, but it was at least more accessible for someone with the right tools and knowledge. However over the past 15 to 20 years, this began to change.

Now, Gordon-Byrne said that even when people can find a way to open these devices efficiently, they still face the challenge of recovering batteries and other components which are often embedded. The inability to replace a part means consumers have to buy a new device and the old one becomes far less valuable or may even end up in a landfill.

"What makes something have market value is the ability to make it work again," she said.

This kind of shift could also help boost local economies. According to analysis from repair company iFixit, 200 repair jobs could be created for every 1,000 tons of used electronics.

Recycling dilemmas

An increased number of affordable replacement components and refurbished devices could potentially reduce the amount of material ending up in the e-waste stream — which would seem to go against the interest of recyclers. Yet earlier this year, the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI) passed a right to reuse policy advocating for just that.

"More and more traditional recycling companies are diversifying their business models to include reuse," said Robin Wiener, president of ISRI, in a statement at the time. "It is essential that they have the legal protections in place that allows the lawful repair and return of these products to the marketplace."

ISRI's policy says that used products should not be considered waste and recyclers should have the right to reuse products. It also says that manufacturers should allow recyclers to bypass digital locks and provide affordable access to parts, schematics, diagnostic software and tools.

Jason Linnell, executive director of the National Center for Electronics Recycling (NCER), said that shredding devices and recovering the metal used to be seen as the preferred method. Though now that certain commodity prices have declined, companies are realizing it may be more profitable to refurbish some of these devices instead.

"The hope is that the more products are easier to repair maybe they can prolong their life before they hit that end of line," said Linnell.

Newer phones or tablets may be worth more if they can be updated and resold rather than recycled, but right now companies have few ways to do that efficiently.

"If they’re trying to turn over many units of the same thing all at once they need to get them repaired and out the door as fast as possible," he said.

While Linnell agreed that some sort of policy change would be good for new devices, he pointed out that this wouldn’t necessarily help with the large backlog of old devices. According to a recent NCER report, U.S. households contain an estimated 3.8 billion devices in use or storage. Some items may have been collecting dust and depreciating for decades, and may not even be worth trying to save. Mobile devices, for example, lose most of their resale value within two years.

On the commercial side, businesses may change their computer system and send a recycler hundreds of the same laptop at once. Yet local residential e-waste collection programs are often overwhelmed with piles of old TVs and other outdated items on which they can't make a profit.

Repair revolution

Increasing reuse and repair won't solve all the challenges of electronic recycling, though a growing number of people agree that it will help. Getting manufacturers to change their stance on the issue has been unsuccessful, so The Repair Association is taking a legislative approach.

Since 2014, "right to repair" or "fair repair" bills have been filed in five states: South Dakota, New York, Massachusetts, Minnesota and Nebraska. None have passed yet, but Gordon-Byrne expects more to be introduced in upcoming legislative sessions.

This is modeled after an effort to change practices in the automotive industry, which has posed similar challenges due to advanced software and components. After Massachusetts instituted a right to repair law in 2013 the automotive industry changed its policy nationwide to avoid a patchwork of further state regulations. Gordon-Byrne thinks with support from the recycling industry, lawmakers and consumers of electronics recycling will eventually be faced with the same choice.

"It really is going to take one state and then the business model falls apart," she said. "What’s the difference between a chip in a car and a chip in a refrigerator and a chip in a cell phone?"