Dive Brief:

- The board of Hennepin County Commissioners in Minnesota voted unanimously Tuesday to instruct officials to begin preparing a closure plan for the county’s waste-to-energy plant, known as HERC. Great River Energy’s contract to operate the facility expires in 2025.

- The plan would explore the procedures needed to close the Minneapolis facility sometime between 2028 and 2040. The county board expects to receive a report on pathways to closure in February.

- Before the vote, commissioners noted that executing a closure plan would require collaboration with local and state officials. “The fact that we are all unified and came together is the easiest of things,” Commissioner Jeffrey Lunde said of the county board on Tuesday. “Now we also need to get cities and the state to also get on board with us.”

Dive Insight:

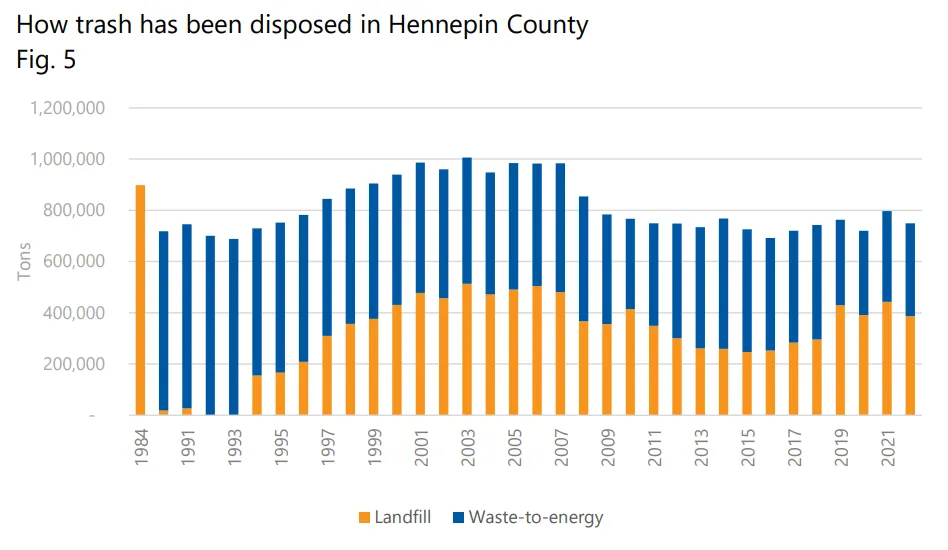

Like other communities looking to transition away from incinerators, Hennepin County faces challenges identifying replacement disposal capacity. The county has struggled to cross the 50% diversion rate threshold for waste despite a goal of reaching a 75% rate by 2030. Even so, the county reached a new recycling rate high in 2020, and environmental advocates believe the Twin Cities area could meet its targets if the county shifts its focus from incineration to diversion.

Hennepin County’s growing waste volume is expected to pose a challenge to shutting the facility. The county generated about 1.27 million tons of waste in 2022, down 2% from the previous year. But projections indicate the county’s waste generation could reach 1.55 million tons by 2042, a 19% increase.

Over the summer, officials discussing the region’s new solid waste policy plan noted that the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency recommended expanding multiple landfills to handle 5.6 million more tons of material in 2021 as tonnage throughout the Minneapolis-St. Paul area increased and a different WTE plant, Great River Energy’s Elk River facility, closed.

The legislation that the county board passed Tuesday acknowledges those challenges while citing the need to protect the community that’s grown up around the HERC facility since it became operational in 1989. In comments, Board Chair Irene Fernando cited the county’s 2020 declaration of racism as a public health crisis as a motivation. She also noted a report issued by the county administrator in September that laid out HERC’s history and the challenges that arise from replacing the facility.

HERC processes a maximum of 365,000 tons of trash annually, a limit set forth in its state permit. The facility generates 200,000 megawatt-hours of electricity annually, a portion of which powers downtown Minneapolis district that includes Target Field, the baseball stadium neighboring HERC that opened in 2010.

Hennepin County acquired the facility from General Electric in 2003 and reached its current operating agreement with Great River Energy in 2018, according to the administrator’s report. That contract is set to expire at the end of 2025. A separate contract for ash disposal, metal recycling and additional metal recovery with SKB Environmental, owned by Waste Connections, is also set to expire at the end of 2025.

About 75% of the waste going to HERC currently comes from Minneapolis, the county seat of Hennepin, with the remainder from other outlying areas. Minneapolis alone sent nearly 80,000 tons of waste to HERC last year, per the report. Currently, nearly 30% of the county’s trash consists of organic material, despite the area’s reputation for a strong organics recycling program. Materials like plastic film, paper and durable plastic that lack recycling options in the county also make up a notable portion of the waste sent to the incinerator.

Closing the facility would introduce both financial and capacity challenges that need to be addressed, according to the county administrator. While the county currently consolidates waste at its Brooklyn Park Transfer Station before sending it to HERC and an area landfill to control trash volumes, it would have no need to do so without HERC and could sell the facility or convert it for a different use.

Rerouting all of the county’s waste to landfills could result in a 30% to 45% increase in the city’s disposal costs, likely passed on to residents, the report noted. And without tipping fees from HERC, the county may need to find alternative funding mechanisms for its existing waste programs.

Financing alternative solutions for waste may be tricky. Earlier this year, a state budget package tied funding for an anaerobic digester to a mandatory closure plan for HERC. The administrator’s report noted that MPCA could reject the county’s solid waste plan if it included steps to close HERC “before waste reduction and recycling rates allowed for a simultaneous reduction in the need for landfilling.”

Nevertheless, Hennepin County plans to thread the needle between moving on from an unpopular facility and scaling up waste diversion initiatives. In its waste section, the county’s climate action plan noted it expected WTE “to decline in importance” as disposal alternatives become more widely adopted. “There is still a lot of trash created by residents and business, and we need to manage it responsibly. HERC makes environmental sense until we have successfully diverted most organic materials which include food waste, paper and wood, from the trash,” the report said.

On Tuesday, county commissioners acknowledged the challenges they will face in shutting down the facility, even as they agreed it was necessary to move forward with the plan.

“There's a commitment to stop burning trash, and we look forward to doing the heavy lifting alongside of community and partners to achieve that goal,” said Board Chair Fernando.