Dive Brief:

- A recently passed bill in the Florida state senate would require municipalities to address material contamination in curbside recycling programs if signed into law. Cities and counties would have to add contamination considerations into their contracts with recyclable material collectors, transporters and processors. The bill also passed in the Florida House.

- As written, the bill makes it so that haulers and MRFs are not considered responsible for the handling of contaminated material as defined by contracts. Contracts would also have to list strategies for reducing contamination, rejecting contaminated material, enforcing strategies and educating the public.

- The bill does not name a statewide contamination standard, but rather leaves it up to each municipality to define the term "contaminated recyclable material" in their collection and processing contracts.

Dive Insight:

It is yet unclear how this bill would play out if Florida Gov. Rick Scott signs it into law. It's also unclear how the new law will affect contracting in the state, and whether it could become a model for others to follow. However, Kevin Kraushaar, Senior vice president for government affairs and general counsel for the National Waste and Recycling Association (NWRA), said this bill was a top priority for the Florida chapter this year.

"Rather than mandates coming down from cities and counties, this bill allows the municipalities and the collectors to work together to come up with procedures that work in those particular communities," Kraushaar told Waste Dive. He said this bill was "trailblazing work" and could be an example for other states to combat contamination.

Defining contamination is an extra step municipalities and private companies will have to agree on, which could draw out any potential agreement. And, while the law aims to improve bale quality by tackling contamination, it could lead to haulers leaving more recycling by the curbside because of perceived contamination; the bill does not set standards as what happens if a hauler and a local government disagree on whether a particular cart or load is contaminated.

Kraushaar declined to speculate on what could happen if there are contaminated loads and collectors choose to not collect recycling in certain communities. He said that NWRA would "rely on the ability of the negotiators and the development of contract language to go forward with what the communities want to do" in those situations.

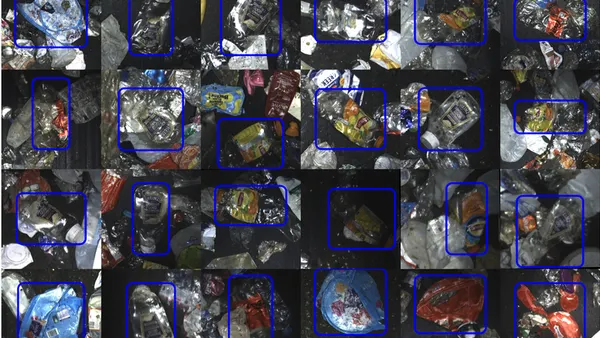

Contamination has become a glaring problem for the recycling industry with the increasing prevalence of single-stream curbside collection. Residential recycling programs used to focus on aluminum, corrugated cardboard and glass, and they usually required customers to separate the materials. That was easy for customers to comprehend, but the addition of new materials over the years has caused growing confusion, especially because each municipality across the country can accept different materials. As of March 1, China's contamination rate narrowed to 0.5%, and any loads not meeting those standards will be rejected. That's a tough, if not impossible, standard for many recyclers to meet.

But even domestically, there has been a push for reducing contamination to increase the quality and value of scrap, particularly plastics and fiber. Clean, homogeneous, high-quality bales garner a significantly higher sales price than dirty, mixed bales. Contamination — either from food debris and inappropriate items, or materials with different plastic resins — makes bales much more difficult and expensive for end users to handle, regardless of whether that end user is a scrap processor or a new product manufacturer. Thus, a growing number of end users are willing to pay more for well-separated, high-quality scrap.

It may make good sense for this kind of system to be demoed in The Sunshine State — contamination makes up about 30% of Florida's recycling stream. The state recently launched an educational campaign to simplify the process and help residents get back to basics with what they leave curbside: aluminum and steel cans, plastic bottles and jugs, paper and cardboard. Individual cities or counties in Florida have taken action to eliminate other items from the stream, such as glass or magazines.