Since the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972, many wastewater treatment plants have operated with a simple environmental trade-off — they treat water from population centers, industrial sources, landfills and elsewhere, and the leftover solids can be sent to farms to use as fertilizer.

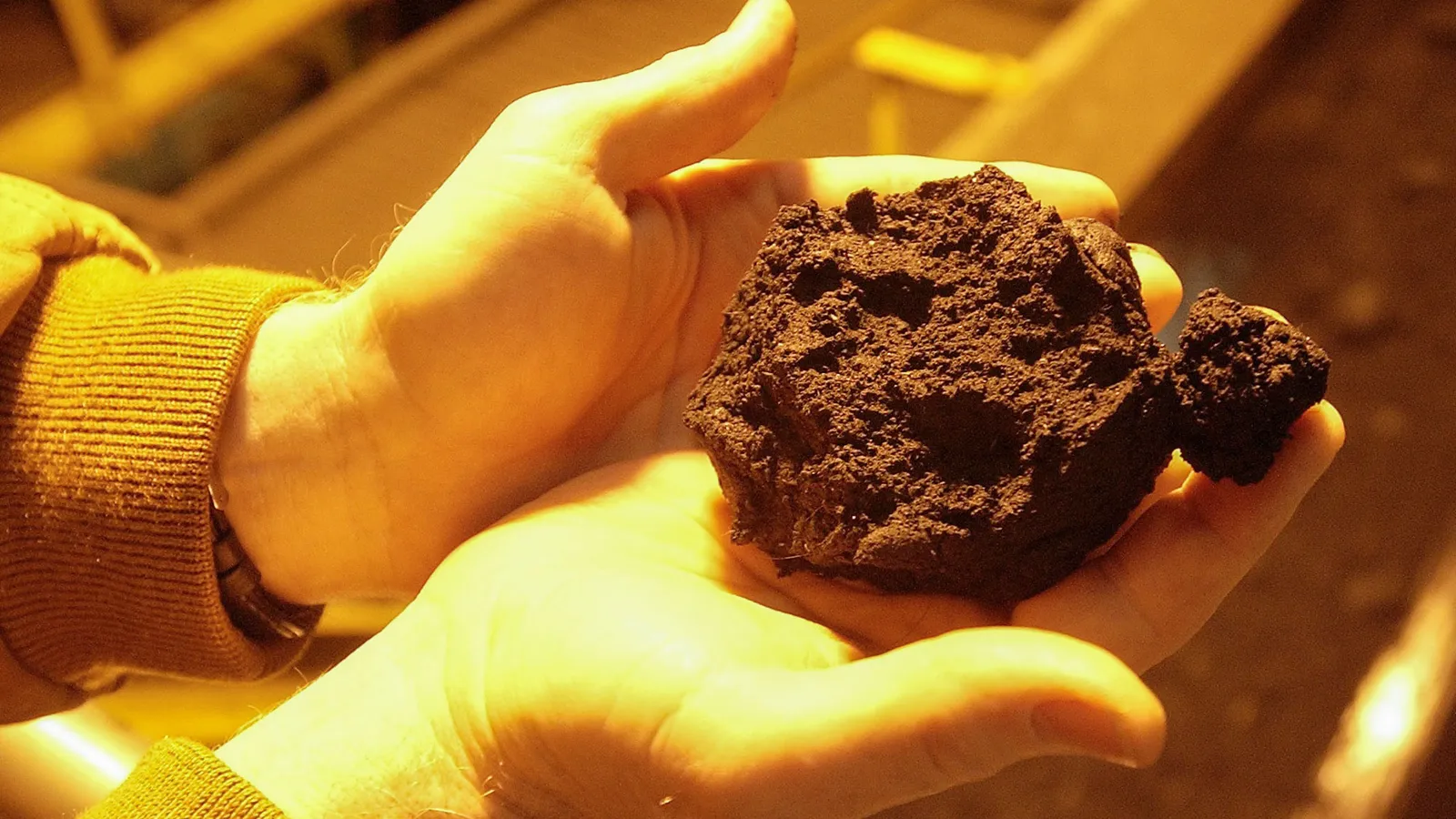

But that arrangement has neared a breaking point in recent years, strained by new understanding of pollutants like PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. In communities around the U.S., the chemicals are exiting the plants via its sludge, known as biosolids, and in some cases contaminating farmland.

The question of where the biosolids can go now — either for treatment or reuse — has left the waste industry and policymakers around the country mired in tough policy decisions.

Some feel left in the dark by the U.S. EPA, which recently argued in court that it’s under no obligation to regulate PFAS in biosolids at all, or even place them on its list of pollutants to watch. Instead, the agency has issued nonbinding guidance on addressing contamination which emphasizes reducing pollutants, as well as monitoring programs and collaboration with manufacturers.

In a statement, an agency spokesperson defended the process, and further noted that any risk reduction requirements will be weighed against “economic costs and treatment feasibility.”

“The presence of a pollutant in sewage sludge alone does not necessarily mean that there is risk to [human health] or the environment from its use or disposal,” Dominique Joseph, a senior communications advisor with EPA, said in an emailed statement.

The agency also said it would finalize a risk assessment this year for the presence of two chemicals in biosolids, PFOA and PFOS, but not others. And while the EPA has issued guidance on PFAS destruction and disposal, many advocates remain unhappy with the lack of a common standard that they feel could compel more wastewater treatment plants to install technology to reduce contamination.

Amid that uncertainty, a growing number of states have begun considering their own bans on land application or more stringent PFAS treatment strategies. They’re weighing public health concerns with the interests of organizations like the North East Biosolids & Residuals Association, which is advocating for methods to treat or reuse biosolids on behalf of its membership of wastewater treatment operators and waste companies.

In Maine, residents have documented serious health and environmental concerns related to high levels of PFAS on certain farms for years. Their exposure led the legislature to start a buyback program for some contaminated farmland and ban the application of biosolids on agricultural land in 2022.

Maine’s ban, LD 1911, was described at the time as the first state law in the U.S. to effectively halt land application. Environmental and public health advocates hailed it as a victory, but they remain frustrated by what they view as an absence of leadership from the federal government.

Kyla Bennett, director of science policy at Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, is representing farmers who are suing EPA to force regulation of PFAS in biosolids. Bennett said the “patchwork approach” to regulation employed so far won’t work because the pollution can cross state lines. And since PFAS lasts for decades, each new patch of contaminated farmland could take years to clean up.

“The bottom line is that farmers and ranchers and consumers are being injured now. Spending several more years studying things and figuring out what to do is not what we need right now,” Bennett said. “It has to stop.”

A crisis in Maine

Amanda Smith, the director of water quality management for Bangor, Maine, oversees the city’s wastewater treatment plant. She said the job’s environmentally friendly-sounding mandate was one of the reasons her brother first got into the industry, and eventually convinced her to join in 2008.

“He said it’s a dirty little secret, these are the best jobs nationwide,” Smith said.

But on Feb. 23, 2023, Smith faced a crisis. The Bangor Wastewater Treatment Plant had a contract with Casella Waste Systems in which the company would take the plant’s biosolids to be prepared for land application, or landfilled since the passage of LD 1911. But Casella abruptly stopped accepting the sludge, saying it could no longer manage it at the Juniper Ridge Landfill.

Smith’s plant had little to no capacity to store its biosolids. In a matter of days, it would exceed what space it had, and begin automatically discharging untreated wastewater into the Penobscot River.

“Bangor has never once gotten a phone call saying, ‘We can’t pick up your biosolids,’” Smith said. “That was a very eye-opening moment. That had never happened before, and it was happening throughout the entire state.”

Within days, the state’s Department of Environmental Protection identified an emergency solution, allowing biosolids from wastewater treatment plants to be shipped up to Canada at significant expense. The legislature also passed an emergency bill, LD 718, later that year. It allowed landfill operators to import out-of-state C&D waste as a bulking material safely landfill the biosolids through July 1, 2025.

The state’s moves bought stakeholders across the treatment and disposal system some time, but questions about solutions and capacity remain.

A report submitted to Maine DEP last December painted a stark picture of the state's capacity to dispose of or remediate contaminated biosolids. Prepared by engineering consulting firm Brown and Caldwell, with support from the Maine Water Environment Association, the report surveyed the state’s regulatory and practical landscape for biosolids management.

The consultants noted that three landfills in Maine "provided for nearly all the biosolids disposal in the state," with the state-owned, Casella-operated Juniper Ridge handling the vast majority of such materials.

However, regional disposal capacity appeared to be shrinking fast. The Hartland Landfill, owned and operated by the town of Hartland, is expected to close by 2033. WM’s Crossroads Landfill is expected to bring a biosolids dryer online in 2025, which would reduce the liquid in and volume of biosolids, but the report predicted it won't fully address the state's needs. Juniper Ridge, which received about 90% of the state’s biosolids in 2022, was expected to fill its remaining permitted capacity by 2028.

That timeline led Brown and Caldwell to assert that without action, biosolids would “need to be sent out of state at greatly increased cost for utilities and ratepayers.”

The consultants provided a series of recommendations to avoid that possibility. Most significantly, they suggested reversing the total ban and setting less stringent contaminant limits or — following an example set by other states — setting interim guidance that would switch to a federal standard once one is finalized.

In a response to the original DEP report, Casella Vice President of Communications Jeff Weld said the company agreed with its criticism of the total ban on land application and its support for an expansion of Juniper Ridge. He also highlighted the company’s recent agreement with Viridi Energy, in which the latter company will put biosolids through its Brunswick, Maine, anaerobic digestion facility before sending the lighter, drier digestate to Juniper Ridge.

“While the passage of LD 718 has allowed for the stabilization of the existing disposal capacity, that was only a temporary measure, and thoughtful consideration for the continued usage of bulking material at the landfill is also a significant part of managing this waste stream as new technologies take time to emerge and LD 718 prepares to sunset,” he added.

On Oct. 2, state regulators signed off on on the first step toward an expansion of Juniper Ridge. Agency officials cited the Brown and Caldwell report in their explanation of the decision, noting the uncertainty around future tonnages of sludge coming from wastewater treatment plants.

Maine's dwindling capacity

-

July 1, 2025

The temporary allowance for landfill operators to use out-of-state C&D waste for bulking expires.

-

2025

Crossroads Landfill’s biosolids dryer is expected to begin operation, adding the ability to shrink the volume of biosolids.

-

2028

Juniper Ridge Landfill is projected to reach capacity without expansion.

-

2033

The Hartland Landfill is expected to close.

-

2038

Juniper Ridge Landfill is expected to reach capacity if an expansion is approved.

Shifting responsibility

Not everyone agrees Casella faced a crisis.

Sarah Nichols, then-director of the Natural Resources Council of Maine's sustainability program, noted in 2022 testimony that if all of the composted or land-applied sludge in Maine in 2020 were instead sent to Juniper Ridge, it would have constituted roughly 2% of the waste accepted there. The landfill already accepted 64,443 tons of sludge in 2020, far more than was composted in the state, according to DEP data cited in Nichols’ testimony.

Landfill experts have documented a rise in disposal of aqueous wastes like wastewater sludge for years, and say there are alternatives to what was approved at Juniper Ridge.

A report from the Environmental Research & Education Foundation found that any number of materials, even off-spec diapers, can be deployed as bulking agents at landfills when necessary. A “bulking agent” is a material that can reduce the level of liquidity in another material to ensure it’s stable when introduced into a landfill, said EREF CEO Bryan Staley, who was a lead author on the report. He said what agent a landfill chooses for the job often comes down to economics.

“It’s basically, what’s the best proverbial napkin for the job? In most cases, it’s the napkin that people have to pay you to take,” Staley said.

Environmental groups view these disposal decisions as important because of what they describe as potential health effects from landfill infrastructure.

Juniper Ridge, for instance, is upstream of traditional Penobscot Nation fishing grounds in Maine. Tribal representatives have spoken out against a proposed contract extension for Casella to continue operating the landfill, as well as its expansion. They alleged that pollutants such as PFAS are leaching from the landfill and contaminating their waterways.

“We live every day with the odors and fumes from the landfill,” Maulian Bryant, a tribal representative, said at a public meeting in February. “The river is part of our ancestral and present-day territory, and the health and well-being of the river has a direct and absolute effect on the health and well-being of our tribal citizens.”

Casella and other landfill operators disagree with this characterization of their operations and describe themselves as passive receivers of PFAS-containing waste. In their view, the PFAS issue is one that needs more attention upstream.

As part of the expansion announcement, DEP said it expects Casella to install a landfill leachate treatment system for PFAS that could address the exposure pathway. Casella’s Weld also said the company was piloting a foam fractionation system at a Vermont landfill that it could replicate in Maine.

“As we move forward with expansion at [Juniper Ridge], plans include designing and installing a system to remove PFAS compounds from landfill leachate produced on site. Like the rest of the industry, we are still in the early stages of understanding the ability and necessity to implement these systems and how to best utilize emerging technologies,” he said in a recent statement.

Trends in other states

Sarah Woodbury, a member of advocacy group Defend Our Health that pushed for Maine’s ban, feels that regulators aren’t moving fast enough to mitigate harm. She said other states are beginning to wake up to the issue.

“Maine might be the [state] that knows that we have contamination and seems like we have the most, but we don't. It's just that we're looking for it,” Woodbury said. “As soon as other states start looking and doing testing, they're going to find the same thing that Maine has: that there's contaminated farmland, that they need to deal with it and it's going to cost a lot of money.”

The use of biosolids has generated controversy in the past — a case concerning biosolids sent from Los Angeles County to another county in California even reached the U.S. Supreme Court — but recent issues are leading to some of the strongest restrictions yet.

A growing number of states have begun setting limits on PFAS in biosolids or banning land application entirely, setting up their own disposal questions.

Connecticut recently joined Maine by passing a total ban on the use or sale of biosolids as a soil amendment, which took effect in October. Massachusetts lawmakers also considered a bill this year concerning PFAS contamination that would have phased out the use of wastewater sludge for any purpose.

To avoid that process, NEBRA has come out strongly against total bans on the land application of biosolids. The organization published op-eds and lobbied against Maine’s ban in 2022. It again rallied its membership — which includes waste companies such as Casella, local water authorities and other entities — against Massachusetts’ bill.

Executive Director Janine Burke-Wells said total bans short-circuit a system that has been in place for decades. She also said that reaching zero levels of PFAS in biosolids is unrealistic at a time when the chemicals are seemingly being found everywhere.

”We have three methods of dealing with it right now: we can landfill it, we can incinerate or burn it, or we can reuse it,” Burke-Wells said in a 2023 interview. “In Maine, there is no incineration, so they limited land application and now they’re down to one leg of the stool.”

Some states have taken a more measured approach.

Stephanie Kammer is the emerging pollutants section manager of Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy, where she helps coordinate the state’s response to PFAS contamination in wastewater.

In 2017, PFAS contamination in fish led Kammer and her colleagues to a chrome plating facility that had been discharging a large amount of the chemicals into a river. That discovery led to a statewide investigation, following which Michigan halted the land application of biosolids from six wastewater treatment plants due to high concentrations of PFOS.

It then embarked on source reduction efforts upstream of the water treatment facilities to reduce concentrations, successfully reducing PFOS contamination by 85% or more at four of the facilities by 2022. Even so, one other facility that successfully reduced its emissions by 54% was “re-exposed to a source of PFAS” that subsequently raised its contamination levels, underscoring the difficulty of continued progress.

“Our facilities took on the challenge and the extra work and were able to pretty successfully demonstrate that reduction at the source is effective in reducing municipal effluent and municipal biosolids [contamination],” Kammer said. “Does it get it all out? No. So there's still work to be done, and it's getting more complicated.”

When Michigan first implemented its PFAS strategy, the amount of land-applied biosolids in the state dropped by nearly half. But since 2018, land application has steadily increased, reaching nearly 90,000 tons in 2022. The state also only requires action for PFOS contamination specifically, though previously said it planned to implement a similar measure for PFOA this year. The state’s interim strategy bans the reuse of biosolids if the material contains PFOS at 125 parts per billion, which it revised down from 150 ppb in 2021.

In the years since their discovery, Kammer and her team have begun sharing their perspectives with colleagues in other states. Some of those states have taken a similar approach to Michigan. Colorado, for instance, is implementing an industrial pretreatment program and studying PFAS concentrations in biosolids.

New York set its own interim guidelines that are more strict than Michigan’s. It bans the use of biosolids if either PFOS or PFOA contamination levels reach 50 ppb. Both New York and Michigan have also set lower limits for the chemicals that would trigger the need for remedial action to reduce contamination.

Finding — and funding — alternatives

Around the country, lawyers are filing an escalating number of lawsuits to assign blame for PFAS contamination and extract payments for those affected.

In Georgia, for instance, the Southern Environmental Law Center successfully sued the city of Calhoun on behalf of the Coosa River Basin Initiative and spurred the implementation of PFAS reduction methods at its wastewater treatment plant. Wastewater treatment plant operators themselves are also now suing the manufacturers of PFAS chemicals, seeking some form of compensation.

Landfills have become embedded in a system where they receive PFAS-laden waste and then send their leachate to wastewater treatment plants, sometimes passing along that PFAS and then potentially receiving it again if they accept biosolids for disposal. That challenge has led the waste industry to push the federal government to recognize their facilities as "passive receivers" of the contamination, which would allow them to avoid responsibility for cleaning up PFAS contamination.

While this treatment comes with a cost, companies largely expect to pass that on to customers. They also see the potential for new revenue from managing PFAS-containing hazardous waste. Environmental services companies like Veolia North America and Clean Harbors are pitching their remediation technologies to wastewater treatment plants.

Landfill operators may also charge wastewater treatment plants higher tipping fees to dispose of biosolids, Jeremy O’Brien, director of applied research at the Solid Waste Association of North America, said during Wastecon on Oct. 24.

“The opportunity is a revenue opportunity,” O’Brien said. “Charge a higher tip fee — like we do for asbestos — for the disposal of those biosolids, and that money can be used to build a PFAS treatment system for leachate at the landfill.”

Since many wastewater treatment plants are run by a public authority and funded by tax dollars, it's local residents who often end up footing the bill for PFAS remediation measures. But others argue the source of these chemicals — manufacturers like 3M and Chemours — should be the ones paying. An increasing number of lawsuits, some successful, have begun to seek that solution.

Back in Maine, wastewater treatment plants are already paying for contamination.

When land application was first banned, local authorities like the York Sewer District began sending more biosolids to the landfill. But landfill tipping fees quickly rose, said Superintendent Phil Tucker. Almost overnight, the annual cost to manage his plant’s biosolids doubled. Today, he said other plants like York’s are “trying to get their biosolids as dry as they can, [but] that costs money.”

“Our plants weren’t designed to remove these chemicals,” Tucker said. “It really shouldn’t fall to the people living here to pay for the cleanup of this, it should fall to those who benefited from it.”

Maine’s DEP has sponsored a pilot to study effluent and begin identifying sources of PFAS contamination in wastewater treatment plants, similar to programs like the one put in place in Michigan. But the question of how these facilities can absorb the cost of managing PFAS pollution without receiving compensation from the source of that pollution remains unanswered.

So far, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act has provided the EPA with $1 billion to help finance water projects that address emerging contaminants like PFAS for five years. The agency said in a statement that over 85% of projects funded by that program in fiscal years 2022 and 2023 were related to PFAS, including “some for biosolids.” The EPA has also made funding available through its Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act loan program for PFAS-related projects.

But observers say a significant amount of funding beyond what they’ve seen from the federal government so far will be needed to manage this growing problem.

Like Bangor’s Smith, Tucker also said he got into the wastewater industry in part because it seemed like an environmentally friendly position. But he laments that PFAS chemicals have caused an existential challenge for his work while generating profits for manufacturers.

“To go along for a long time thinking you’re doing something that’s good for the environment, and to have all of that stop because of greed, to be frank, it’s upsetting,” Tucker said.