When AMP Robotics started in 2014, robots and artificial intelligence were still uncommon enough that recycling facilities often announced each new installation and even gave their robot a name.

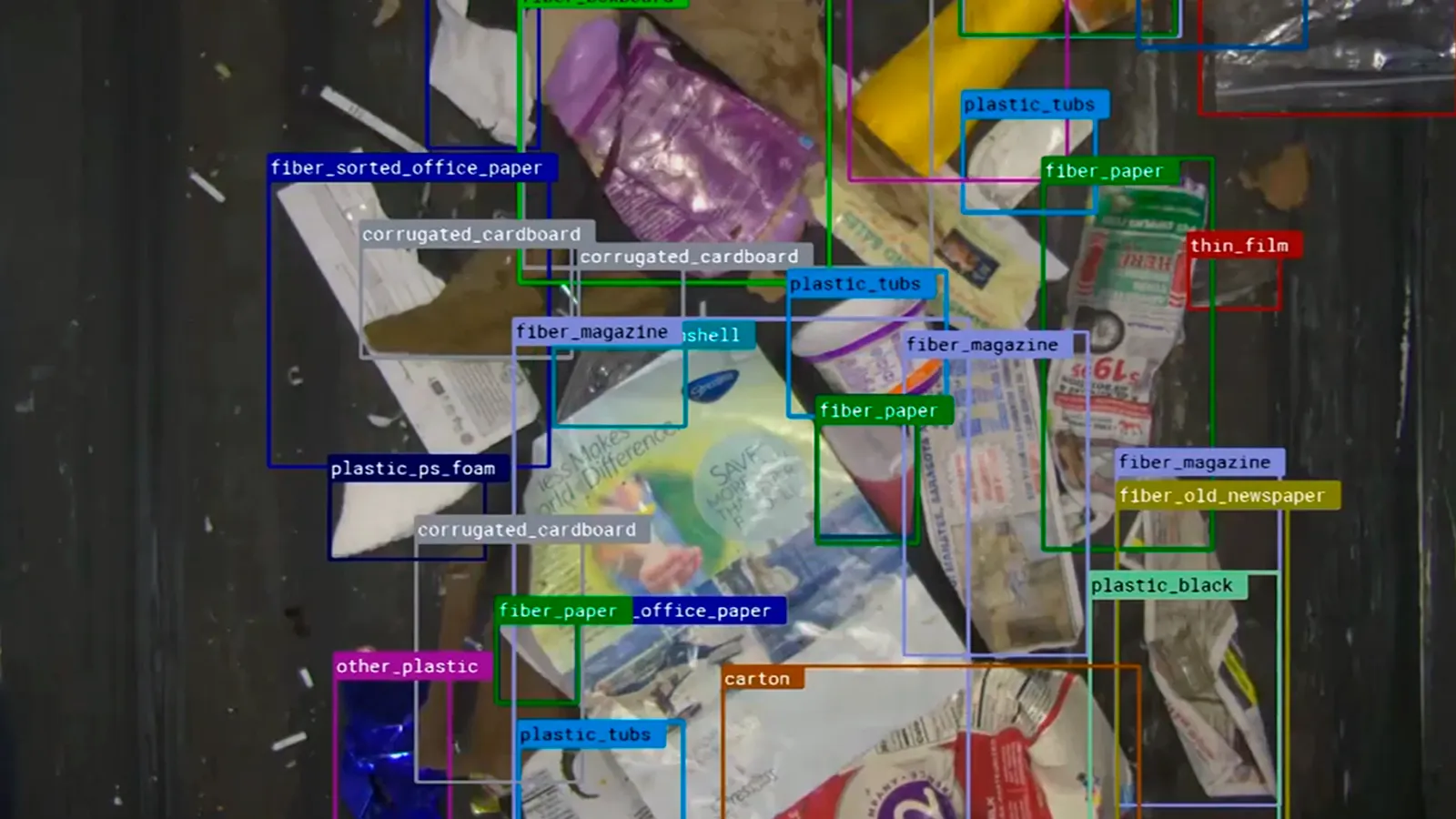

Today, AMP still names the robots it builds, but that’s mostly to help employees differentiate orders when managing the shipment of multiple similar-looking pieces of technology. To date, AMP has installed a fleet of almost 300 robots in facilities around the world, and it has further plans to expand into the European market. The company says its AI-powered “neural network,” shared by all the robots, can recognize about 75 billion objects a year.

In November, AMP officially opened its nearly 84,000-square-foot headquarters in Louisville, Colorado, which the company says gives it the R&D, manufacturing and demonstration space necessary to carry out some of its long-term plans. Though AI-assisted robotic technology is still the company’s focal point, CEO Matanya Horowitz has moved in recent years to expand its horizons, most recently by opening three company-run secondary sortation facilities: one a few miles away in Denver and two more in Cleveland and Atlanta. Breaking into that kind of operation is a fairly unique move among MRF equipment companies and within the industry in general.

In the near future, AMP aims get involved in building single-stream MRF facilities, Horowitz said. Details on what those MRF projects could look like, or whether AMP will operate them or partner with other waste companies on certain elements, are still in development. Yet Horowitz said it’s a logical next step for the company.

“We think we have something very special when it comes to the whole facility, like the fact that you can be fully automated,” said Horowitz. “It really changes how you think about running 24/7. It really changes the economics of smaller recycling programs, changes the economics of where it's viable to put these facilities. We can start to see a path to making really substantive structural change in the industry.”

Investors have recently put their faith in the company with new rounds of venture capital funding. AMP announced earlier in May that it received series C funding from the Microsoft Climate Innovation Fund, bringing in a total of $99 million for the round when combined with investments led by Congruent Ventures and Wellington Management.

The funding represents a major step forward from the early years of the company, when AMP received smaller contributions from the National Science Foundation and the Colorado Office of Economic Development and International Trade that at the time served as an important boost.

AMP plans to eventually go public, “but I wouldn't say that that's a near-term thing. We’re not ready yet,” Horowitz said. “We have hundreds of robots out there. We have whole facilities now. And so bringing on additional capital to scale that further is really the goal.”

Space to experiment

AMP has designed its headquarters facility to have space for all the innovations it hopes to build. In addition to providing offices for its 200 employees, the building is a demonstration center that allows customers like brands and packaging producers to test their materials on different machines or experiment with recent advancements.

The facility also houses the company’s R&D functions and engineering lab, where AMP develops, tests and adjusts technology upgrades or brand-new designs.

On a recent day, Alex Kee, AMP’s senior mechanical engineer, switched on one of the company’s Cortex robotic sorting systems similar to the type installed in most customers’ facilities. Part of the company’s business model is being able to upgrade fleet software with new features, such as one AMP is currently refining: an “advanced targeting” algorithm that helps make the robot’s grip more accurate.

Kee brought up a heat map on a large screen, which showed a crushed HDPE container on the belt. Glowing light-colored spots indicated ideal flat spots for the robot to grip, while darker areas showed folds and creases that would be tricker places to grab. Once optimized, the technology could increase pick precision for the material between 5% and 10%, he said.

In another corner of the lab, the company’s new Cortex-C was sorting a sample set of bottles, cans and containers. The new sorter is a lightweight, belt-mounted version of the original Cortex. Although it operates about 20% slower than its larger cousin, Horowitz said it can replace at least one manual sorter and fit into tighter spaces at MRFs. AMP officially announced the new model at the beginning of May.

Focusing on film

Another piece of equipment in the lab started as a bespoke R&D project: the Vortex, a sorter that hovers over the belt to suck up film plastic. It was originally developed as part of AMP’s Customer Innovation Program, which works with industry stakeholders to build new technology. Engineers started thinking about how to use the Vortex to solve film contamination issues at AMP’s own secondary sortation facilities, said Jake Fitzgerald, director of hardware engineering.

Some of the secondary facilities had up to 10% film in their input stream, an amount that would be “catastrophic” for a primary MRF, Horowitz said. “We wanted [the Vortex] for ourselves pretty badly because we’re processing much more residue” than a typical MRF, he said.

Only a few Vortex sorters have been deployed so far, including one at a Waste Connections facility in Pennsylvania, Fitzgerald said. Waste Connections announced last year that it had either ordered or deployed at least 50 AMP sorters in the last few years, making them AMP’s largest customer.

Horowitz said the company is also positioning itself to capitalize on the industry’s increased interest in film sortation, as companies like WM partner with Dow on curbside film collection and major plastic producers target film plastic as a possible chemical recycling feedstock.

AMP is a member of The Recycling Partnership’s Film and Flexibles Recycling Coalition, which is working on ways to increase curbside recycling and find end markets for film and flexible products.

“We're trying to solve a couple different things for people. One is the MRFs just want the film out of the system. Then there are the people buying the film who want high-quality film,” Horowitz said.

At the same time, brands are using more flexible packaging than ever before. “There’s a real need to make that compatible with the existing recycling industry,” he said.

Whether a MRF treats items like flexible packaging as a commodity or as contamination, Horowitz wants AMP to be able to adjust the technology for either outcome. AMP’s work in secondary sortation has already challenged the equipment to sort though dirtier and dirtier material. It’s operationally challenging, but it also teaches the AI and robotics to work efficiently in harsh conditions. That could help other MRFs when handling periods of high contamination, he said.

“Contamination can kill recycling programs,” Horowitz said. “You still want all the education programs to help, and you still want to have the value of the recyclables be as high as possible, but [the technology] can at least help you be a little bit more resilient if you don't get the material you want.”

The future of AI in recycling

AI capabilities are at the heart of AMP’s operations, but recent congressional hearings and discussions over how to regulate other forms of AI, like ChatGPT, have started national conversations about what role AI will play in the future.

Horowitz said AMP already faces U.S. export restrictions due to the AI it uses — it can’t ship to places like Iran and North Korea, for example — but he’s not concerned about the company’s ability to continue developing and improving AI capabilities in coming years.

“It's something we follow, but it's not going to substantially change our direction, and it certainly will not create any issues for the deployment of the technology,” he said. “It's actually a very exciting time to be in AI, and we're really well placed to take advantage of it.”