Now that the U.S. EPA has made PFAS an enforcement priority, the waste industry hopes the strategy can help reduce the amount of PFAS-containing materials entering waste sites while also being protected from certain liability.

The EPA recently announced a specific PFAS enforcement focus as part of its updated National Enforcement and Compliance Initiatives, which it says will consist of cracking down on entities “who significantly contributed to the release of PFAS into the environment.”

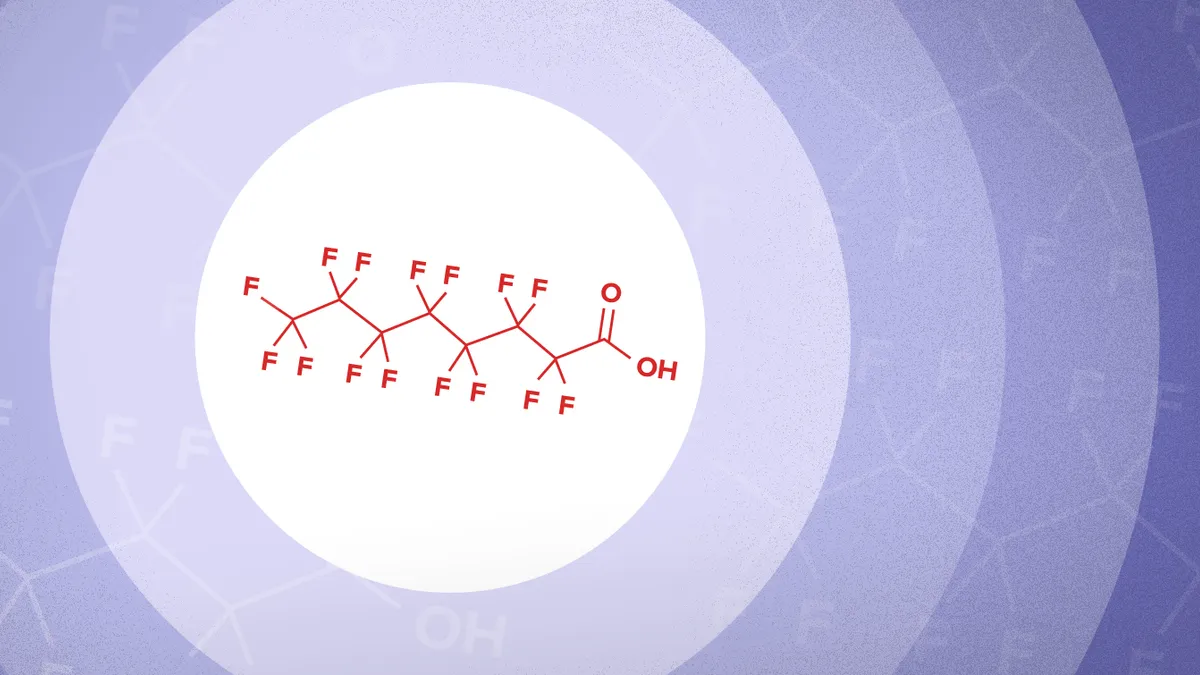

It’s unclear how directly the new PFAS enforcement initiative — set to last between 2024 and 2027 — will affect the waste industry, but experts say the initiative might more quickly motivate manufacturers that use PFAS in their products to find alternatives, thus reducing the amount of PFAS-containing material that will eventually enter waste facilities. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances are found in everything from food packaging to cookware and apparel.

The EPA has said it intends to center its PFAS enforcement priorities on “major manufacturers and users of manufactured PFAS” as well as industrial sites and federal facilities the agency says are a significant source of PFAS.

Waste industry groups generally support EPA efforts to prevent PFAS pollution, but have called for the EPA to direct much of its scrutiny upstream at manufacturers instead of at “passive receivers” such as waste sites, saying they can’t control the fact that PFAS-containing items enter their landfills.

The industry also hopes to avoid potential liability once the EPA designates two types of PFAS as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act known as Superfund. The EPA is now expected to publish the final rule in February 2024.

The EPA didn’t specifically reference the waste industry in its NECI announcement, but said it likely wouldn’t pursue entities where CERCLA regulations may not directly apply, such as farms, water utilities, airports and local fire departments. Though the waste industry wasn’t named in the NECI, Doug Benevento, a partner at Holland & Hart and a former EPA Region 8 Administrator, said the administration has “tacitly recognized” that entities such as landfills are handling PFAS in “products they didn’t manufacture and products they didn’t need or want in their feedstocks.”

Earlier this year, industry groups asked Congress for help exempting composters and operators of solid waste facilities from responsibility for “costs and damages” related to certain PFAS releases in the environment under the Superfund rule. That led to the introduction of the Resource Management PFAS Liability Protection Act, led by Sen. Cynthia Lummis, R-Wyo., and John Boozman, R-Ark. It’s part of a bill package that also seeks liability exemptions for agriculture and water treatment sectors, as well as entities such as fuel depots, airports and refineries that are required by law to use firefighting foam known to contain PFAS.

The Environmental Working Group has criticized some efforts to carve out Superfund exemptions, saying that while Lummis’s bill covers “a handful of sympathetic industries,” the legislation could create a slippery slope for bad actors to also avoid legal liability for PFAS pollution they helped create.

“The PFAS crisis is outrunning the federal response,” said John Reeder, EWG’s vice president of federal affairs, in a statement, adding that legislation that creates “PFAS loopholes in our federal cleanup law is a step backward for communities that have waited for so long” for enforcement.

Cally Edgren, senior director for sustainability at Assent, said manufacturers that use PFAS in products or processes may not see federal enforcement strategies like the EPA’s as particularly influential in changing how they do business. That’s because industries are likely to ask regulators for certain exemptions, saying they manufacture products that need certain PFAS to work correctly and don’t have a readily available alternative.

However, numerous PFAS-related lawsuits and pressure from state laws have made it harder to access PFAS-containing ingredients, meaning companies have had to redesign their products or processes with PFAS-free alternatives out of necessity. They’re also planning ahead to determine if product — such as a machinery lubricant that contains PFAS — may be discontinued in the future due to a lawsuit or an eventual federal ban.

“That has been way more of an influential driver than regulations. Regulations can be negotiated with regulators, but supply chain obsolescence cannot,” Edgren said.

Though the EPA’s enforcement strategy is a federal action, Benevento expects heightened scrutiny is likely to come from the states, many of which have stricter PFAS rules on everything from drinking water to packaging.

It’s common for the U.S. EPA to sit down with administrators from regional offices and state entities to get on the same page about inspection and enforcement priorities, “and they will likely be pushing the states, saying, ‘Hey, we need to see more on PFAS prioritization,’” he said.

States are also able to more quickly pass laws based on advocacy from health and environmental advocates, which is the case for about 16 states that have either banned or restricted PFAS in food packaging or are in the process of doing so.

At the same time, companies are phasing out PFAS-containing materials in food packaging amid pressure from consumers and other advocates.

Though the EPA enforcement announcement alone likely won’t move the needle on reducing PFAS production, Benevento and Edgren said it’s one important tool in the toolbox.

“If you're in the business of handling PFAS, you should be aware of this and you should expect that there's going to be heightened scrutiny,” Benevento said.