Dive Brief:

- The U.S. EPA released a pair of reports on Thursday that reset the table for food waste reduction efforts. The analysis found that 58% of the fugitive methane emissions from MSW landfills come from food waste, and reexamined the life cycle impacts of different ways to address organic waste to prevent more of those emissions.

- In its landfilling report, the agency found that half of the methane produced by landfilled food waste is released in the first three-and-a-half years after the waste is deposited. The report concluded that while landfill gas collection systems are improving, they’re often installed too late or are too inefficient to capture food waste emissions.

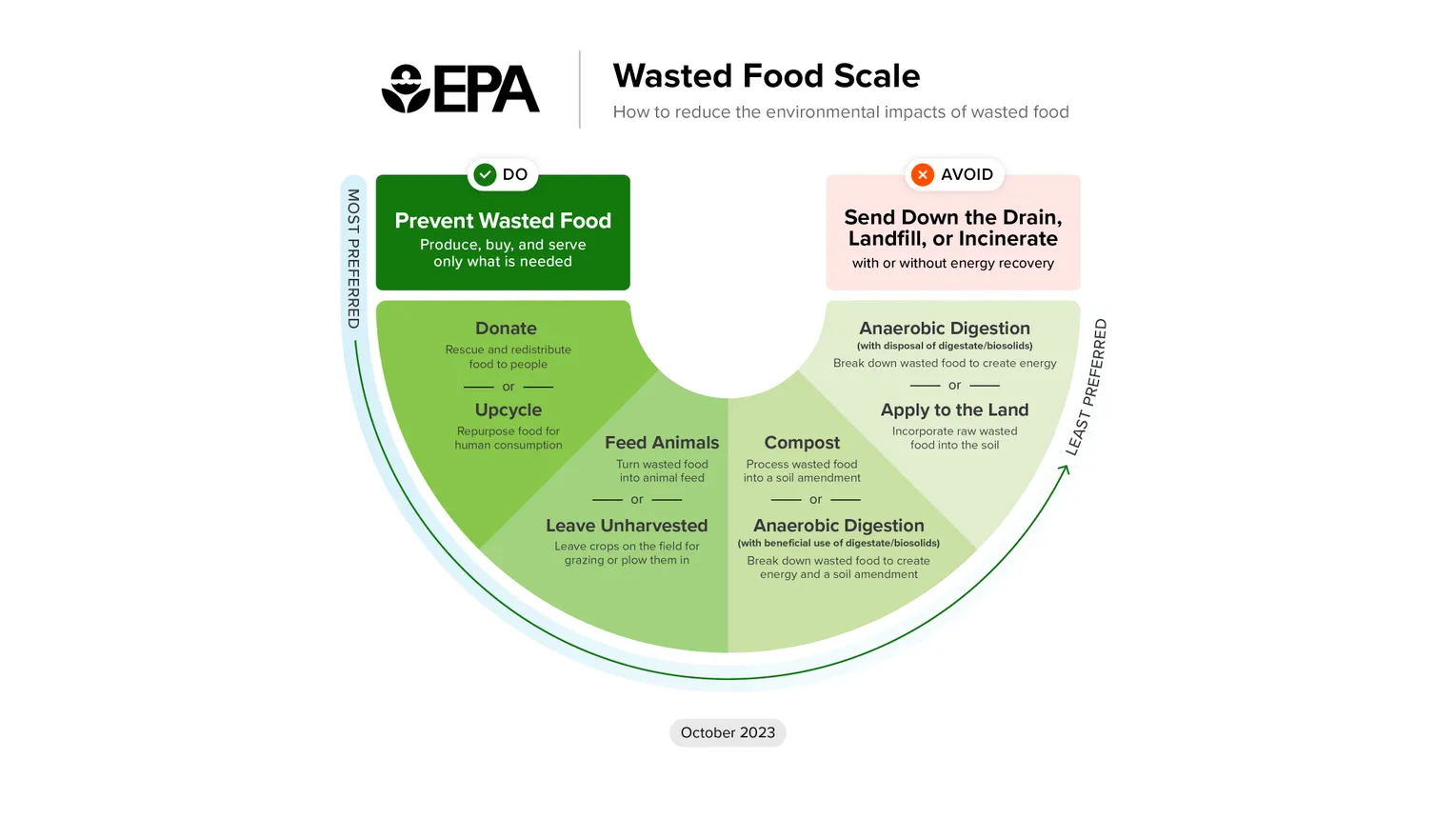

- In another report on food waste management pathways, the EPA revised the hierarchy it has used to rank the preferred outcomes for organics since the 1990s. In a new, more nuanced model, the EPA is putting renewed attention on anaerobic digestion and is doubling down on its support for food waste prevention, donation or upcycling over industrial management pathways.

Dive Insight:

The new reports come amid rising interest in addressing organic waste as a way to reduce emissions from the waste industry. The EPA found that 62.5 million tons of food waste was landfilled in 2020, more than double what was landfilled in 1990.

That waste, which makes up more than 24% of total landfill waste, results in a significant amount of emissions before landfill gas collection systems are installed, making efforts to get emissions from the sector under control difficult.

Those emissions are significant — landfills are the third-largest source of methane emissions from human activity in the U.S., and models estimate that methane gas is up to 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas. The issue has attracted the attention of multiple administrations, including the Biden administration, which released a cross-industry Methane Emissions Reductions Plan in 2021 and joined a pledge to reduce global methane emissions 30% by 2030 from 2020 levels.

To address landfill methane emissions, waste industry heavyweights and energy companies have poured money into landfill-gas-to-RNG collection systems in recent years. Government incentives have encouraged the practice as a means of displacing fossil fuels and capturing damaging emissions before they enter the atmosphere.

But the EPA now says those measures, while necessary for the climate and often lucrative for industry, are not enough to address the scale of wasted food. The new Wasted Food Scale provides additional insight into the best forms of deriving beneficial use from food, discourages in-sink disposal, and reemphasizes prevention, donation, feeding animals or other means of getting the food consumed as the best means of addressing the issue.

“Wasted food is a major environmental, social, and economic challenge,” EPA Administrator Michael Regan said in a statement. “These reports provide decision-makers with important data on the climate impacts of food waste through landfill methane emissions and highlight the urgent need to keep food out of landfills.”

The new EPA ranking pays closer attention to industrial means of food waste management that have become more prevalent since the agency developed its previous Food Recovery Hierarchy. Among them, anaerobic digestion has become much more common and the agency decided to rank the practice on its own in the new model. Other methods, like land application, sewage or wastewater treatment, leaving crops unharvested or plowed in and upcycling were also added.

In its report, the agency also analyzed the prevalence of the 11 food waste management pathways it ranked. The EPA estimates that over one-third of the food produced in the U.S. overall goes uneaten, and 60% of food that is wasted (i.e. not prevented through source reduction) goes to landfills.

Continued landfilling of food waste has also led to increasing methane emissions from food waste. From 1990 to 2020, total methane emissions from landfills declined by 43% while methane emissions from landfilled food waste increased 295%.

While the reports provide new details on the impacts of food waste, efforts to address the issue have been ongoing for years. The U.S. set a goal to halve food waste by 2030 in 2015, but the most recent data suggests the amount of wasted food per capita has actually increased since then.

If the U.S. had halved its food waste in 2015, when the goal was announced, it would have saved 77 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2020, equal to emissions from 21 coal-fired power plants, the agency noted in its landfilling report.

“Given the significant resource inputs (land, water, fertilizer, etc.) used to produce and deliver food to consumers, to then have it go to waste and be disposed in a landfill, generating methane emissions, compounds the environmental impacts of food waste,” the landfilling report concludes.